Writing Friendly Command Line Applications

Let me tell you a story…

In 1986 Knuth wrote a program to demonstrate literate programming.

The task was to read a file of text, determine the n most frequently used words, and print out a sorted list of those words along with their frequencies. Knuth wrote a beautiful 10 page monolithic program.

Doug Mcllory read this and said

tr -cs A-Za-z '\n' | tr A-Z a-z | sort | uniq -c | sort -rn | sed ${1}q

It’s 2019, why am I telling you a story that happened 33 years ago? (Probably before some of you were born). The computation landscape has changed a lot… or has it?

The Lindy effect is a concept that the future life expectancy of some non-perishable things like a technology or an idea is proportional to their current age. TL;DR - old technologies are here to stay.

If you don’t believe me, see:

- oh-my-zsh having close to 100,000 stars on GitHub

- Data Science at the Command Line book

- Command-line Tools can be 235x Faster than your Hadoop Cluster

- …

Now that you are convinced, let’s talk on how to make your Go programs command line friendly.

Design

When writing command line application, try to adhere to the basics of Unix philosophy

- Rule of Modularity: Write simple parts connected by clean interfaces.

- Rule of Composition: Design programs to be connected with other programs.

- Rule of Silence: When a program has nothing surprising to say, it should say nothing.

These rules allow you to write small program that do one thing.

- A user asks for support of reading data from REST API? Have them pipe a

curlcommand output to your program - A user wants only top n results? Have them pipe your program output through `head

- A user wants only the second column of data? Since you write tab seperated

output, they can pipe your output via

cutorawk

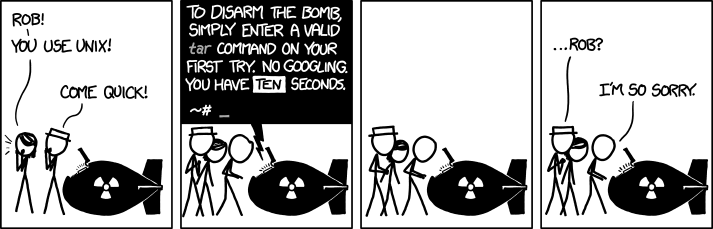

If you don’t follow these and let your command line interface grow organically, you might end up in the following situation

Help

Let’s assume your team have a nuke-db utility. You forgot how to invoke it

and you do:

1 2 |

$ ./nuke-db --help database nuked |

Ouch!

Using the flag, you can add support for --help in 2 extra lines of code

|

|

Now your program behaves

1 2 3 4 |

$ ./nuke-db --help Usage of ./nuke-db: $ ./nuke-db database nuked |

If you’d like to provide more help, use flag.Usage

|

|

And now

1 2 3 4 |

$ ./nuke-db --help usage: ./nuke-db [DATABASE] Delete all data and tables from DATABASE. |

Structured Output

Plain text is the universal interface. However, when the output becomes complex, it might be easier for machines to deal with formatted output. One of the most common format is of course JSON.

A good way to do it is not to print using fmt.Printf but use your own

printing function which can be either text or JSON. Let’s see an example:

|

|

Then

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

$ ./finfo finfo.go

mode: -rw-r--r--

size: 783

dir: false

modified: 2019-11-27 11:49:03.280857863 +0200 IST

$ ./finfo -json finfo.go

{"dir":false,"mode":"-rw-r--r--","modified":"2019-11-27T11:49:03.280857863+02:00","size":783} |

Progress

Some operations can take long time, one way to make them faster is not by optimising the code but by showing a spinner/progress bar. Don’t believe me, here’s an excerpt from Nielsen research

people who saw the moving feedback bar experienced higher satisfaction and were willing to wait on average 3 times longer than those who did not see any progress indicators.

Spinner

Adding a spinner does not require any special packages:

|

|

Run it and you’ll see a small spinner going.

Progress Bar

For a progress bar, you’ll probably need an external package such as

github.com/cheggaaa/pb/v3

|

|

Run it and you’ll see a nice progress bar.

Conclusion

It’s almost 2020, and command line applications are here to stay. They are the key to automation and if written well, provide elegant “lego like” components to build complex flows.

I hope that this article will prompt you to be a good citizen of the command line nation.

About the Author

Hi there, I’m Miki, nice to e-meet you ☺. I’ve been a long time developer and have been working with Go for about 10 years now. I write code professionally as a consultant and contribute a lot to open source. Apart from that I’m a book author, an author on LinkedIn learning, one of the organizers of GopherCon Israel and an instructor. Feel free to drop me a line and let me know if you learned something new or if you’d like to learn more.