Atlas: Building with Rails and Go Microservices

Atlas is a recently announced service by HashiCorp that provides a single platform to take an application from development through to production. The complexity of the problem makes Atlas a sophisticated web service that is composed of many moving pieces. This article covers the design of Atlas, and specifically the use case of pairing a front-end Rails application with a collection of Go microservices in the backend.

Background

At HashiCorp, we are big fans of Go. Most of the tools we build are done in Go, so when we started building Atlas it seemed only natural to build it entirely in Go as well. We are also big proponents of service oriented architectures where many loosely coupled services work together. This is also visible in the design of our open source products as multiple highly focused projects aimed at solving specific problems. Go is a great fit for building these micro services for many reasons, but critically it has the right balance of developer productivity and runtime performance.

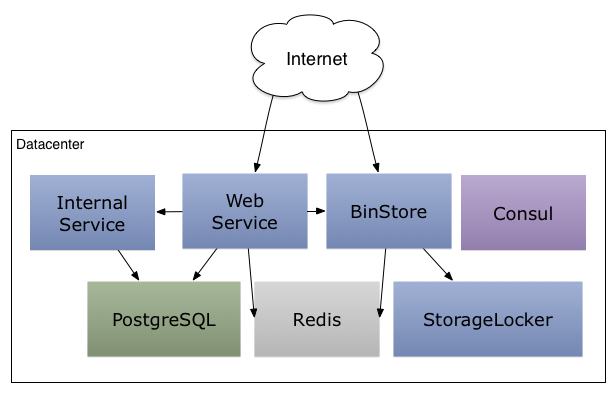

The initial architecture of Atlas (then Vagrant Cloud) was composed of a few backing stores (PostgreSQL and Redis then), many stateless Go services, all linked together by Consul. There were a few Internet-facing Go services, specifically the web service and the BinStore service (previously discussed here). The remaining services were internal only and used to decompose business logic into smaller pieces.

While this architecture worked, we were frustrated by a number of different issues. Having previously developed large sites in both Rails and Django, doing serious web development in Go felt like a major step backwards for productivity and the availability of libraries for common patterns. Instead of simply importing a gem, we found ourselves spending hours writing new libraries or adapting existing ones to fairly vanilla use cases.

The second major issue was around modeling interactions with our databases. At the time, there were no compelling ORMs and building one didn’t seem prudent. Instead we built a simple collection of SQL files for database setup and migrations. Within the services we had used shared structs to model rows and hand wrote SQL for any database interactions. This quickly become a mess to maintain, and a point of friction for iterating quickly. Small changes in our data model now become an ordeal.

After a few weeks, we decided to step back and re-evaluate our design decisions. For almost all of our services, Go seemed like the right choice, but the web service was particularly painful for at least those two reasons. We decided it was time to try something new. This is not a knock on Go or its community, but rather an honest evaluation of the maturity of the web developement ecosystem at the time.

Migrating to Rails

Once we decided to evaluate other technologies for our web service, we had a few choices. Based on having Rails experience and the maturity of that tooling we saw it as the most pragmatic option. As we began our initial port, we realized that over two weeks worth of work in Go had been replaced in just a few hours in Rails. We were sold.

As we completed our migration to Rails, were able to dramatically reduce the lines of code we had to maintain by leveraging the community tooling. Our bespoke SQL migration system could be replaced with the built-in Rails migration system as well. Instead of writing SQL by hand we were able to model our objects and use ActiveRecord to automatically generate queries. This was far less error prone and allowed us to iterate more quickly.

With this migration, we decided to encapsulate our database as much as possible, and ensure that Rails was the only system that interacted with it. Any internal services that previously would query the database were updated to instead use private APIs of the Rails app to ensure all access went through a well-defined interface. This allowed us to change our data model without fear that random services would suddenly break.

A Pinch of Rails, a Sprinkle of Go

While we found that moving our web service to Rails was a huge boost in productivity, we’ve continued to use Go to build all our internal services. Over time we’ve built shared libraries that make it incredibly simple for us to build new services.

Our common pattern for adding features to Atlas is to separate the user interaction from the business logic and background processing. All the user interaction and view rendering is done in Rails, which you could argue is a hyper-optimized DSL for web development. The business logic and background work is done in small Go services.

The Rails application will react to user interaction or API events by calling upstream to the appropriate backend services. Any service that needs to be invoked by Rails provides a JSON over HTTP API. Using a common library in Rails, we can discover these backends using Consul and make the RPC call. This has been a simple and robust pattern that we can re-use across many of our services.

A few of our internal services don’t fit into the request/response model, and instead are more like worker pools. For those services, we decouple the Rails application by using an intermediary RabbitMQ. The pattern we use is to model these jobs as a finite state machine (FSM) (using the AASM gem) so that we can intelligently retry under different failure conditions. Rails creates a database model to track the FSM, and enqueues the job in RabbitMQ. Downstream consumers eventually begin processing the work, and call internal Rails APIs to change the FSM state. In the case of a queue loss (RabbitMQ node failure) we can use the FSM state to rebuild the state of the broker.

With both the request/response and worker pool pattern we’ve built re-usable libraries that let us quickly build clients for our new services in both Go and Rails. This allows us to focus on the business logic and features instead of the boilerplate of gluing various systems together.

Conclusion

We are huge fans of Go at HashiCorp and use it for almost every new service or tool we build. For the most part, this has been extremely successful, with the exception of our web servers. For our use case, using Rails increased our productivity and reduced the code we had to maintain. We’ve standardized the interaction between Rails and our Go services and built libraries around those patterns. In turn, it has become painless to build new services in Go that all work together. All this allows us to ship features quickly and keep the infrastructure simple and modular.