Go Advent Stocking Stuffer Bonus - Ginkgo and Gomega: BDD-Style Testing For Go

Ginkgo and Gomega: BDD-Style Testing For Go

Agile software development is all about discipline, and disciplined agile developers test-drive their code: with a comprehensive test suite, refactoring and adding new features becomes substantially less stressful and time-consuming. Moreover, a well-groomed, lovingly maintained test suite can eloquently describe a codebase’s behavior; thus the test suite becomes a living source of documentation making it easier for developers to communicate intent with one-another.

Testing in Go

In Go, of course, testing is a first-class citizen. gotest` makes running your tests trivial and the new test coverage tool is a great addition to the Go ecosystem. But Go’s built-in test infrastructure is (intentionally) limited: Go provides XUnit-style tests with no shared setup/teardown support and no matcher/assertion library. To understand the implications of these limitations, let’s look at a somewhat trivial example.

Say we have a User object with FirstName and LastName fields and a FullName() method. To fully describe FullName() we need to consider its behavior in four circumstances: when both FirstName and LastName are provided, when only one or the other is provided, and when neither are provided. Here’s what the tests might look like:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 |

package user_test import ( "testing" "user" ) func TestUserFullName(t *testing.T) { u, err := user.New() if err != nil { t.Errorf("Got an unexpected error: %v", err) } u.FirstName = "Peyton" u.LastName = "Manning" fullName := u.FullName() if fullName != "Peyton Manning" { t.Errorf("Expected '%s' to be Peyton Manning", fullName) } } func TestUserFullNameWithoutLastName(t *testing.T) { u, err := user.New() if err != nil { t.Errorf("Got an unexpected error: %v", err) } u.FirstName = "Peyton" fullName := u.FullName() if fullName != "Peyton" { t.Errorf("Expected '%s' to be Peyton", fullName) } } func TestUserFullNameWithoutFirstName(t *testing.T) { u, err := user.New() if err != nil { t.Errorf("Got an unexpected error: %v", err) } u.LastName = "Manning" fullName := u.FullName() if fullName != "Manning" { t.Errorf("Expected '%s' to be Manning", fullName) } } func TestUserFullNameWithNeither(t *testing.T) { u, err := user.New() if err != nil { t.Errorf("Got an unexpected error: %v", err) } fullName := u.FullName() if fullName != "" { t.Errorf("Expected '%s' to be empty", fullName) } } |

There’s a lot of repetition here: each test creates a new user (u, err := user.New()), each test checks the resulting error (if err != nil...), and each test must manually provide a failure string t.Errorf("Expected '%s' to be ...", fullName). Moreover, the documentation power of the tests is limited: the description of each test’s scenario is awkwardly stuffed into the Test... method name and the if statements need to be parsed to glean the expected behavior of FullName.

Go’s authors propose solving the repetition problem using table-driven tests. Here’s our example recast as a table-driven test:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 |

package user_test import ( "testing" "user" ) var fullNameCases = []struct { FirstName string LastName string Result string }{ {"Peyton", "Manning", "Peyton Manning"}, {"Peyton", "", "Peyton"}, {"", "Manning", "Manning"}, {"", "", ""}, } func TestUserFullName(t *testing.T) { for _, fullNameCase := range fullNameCases { u, err := user.New() if err != nil { t.Errorf("Got an unexpected error: %v", err) } u.FirstName = fullNameCase.FirstName u.LastName = fullNameCase.LastName fullName := u.FullName() if fullName != fullNameCase.Result { t.Errorf("Expected '%s' to equal '%s'", fullName, fullNameCase.Result) } } } |

Now the repetition problem is solved, but at what cost? The test is harder to read and filled with infrastructure code that isn’t about the behavior of the method being described; also, it is no longer possible to eloquently document the significance of the various edge cases. Moreover, we are still manually rolling our own failure messages – how do we ensure consistency and quality error messages across our test suite? For example, the if err != nil { t.Errorf(...)}` three-line stanza appears nearly 500 times - in various forms - in Go’s own test suite!

Ginkgo and Gomega: a different testing style for Go

When I first started writing Go code as an engineer at Pivotal Labs working on Cloud Foundry I spent time trying to grow accustomed to the Go way of writing tests, but I quickly found myself missing the more expressive, BDD-style, testing frameworks I’d grown accustomed to. It is out of a deep respect for Go, and a desire to learn the language at a deeper level, that I began working on Ginkgo, a BDD-style testing framework, and Gomega, a companion matching library. The fact that it was possible (even easy!) to write these packages is a testament to Go’s flexibility.

Ginkgo provides you with an intuitive, semantic, DSL to expressively describe the behavior of your Go code. Gomega gives you a rich library of flexible one-line assertions with consistent, descriptive, error reporting (and makes it very easy to write your own custom matchers). Despite being quite young, both packages have a comprehensive and mature feature set and extensive documentation Ginkgo and Gomega).

Here is our FullName() example written using Ginkgo and Gomega:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 |

package user_test import ( . "github.com/onsi/ginkgo" . "github.com/onsi/gomega" "user" ) var _ = Describe("User", func() { var u *user.User BeforeEach(func() { var err error u, err = user.New() Expect(err).NotTo(HaveOccurred()) }) Describe("Full Name", func() { Context("With a first and last name", func() { It("should concatenate the names with a ' '", func() { u.FirstName = "Peyton" u.LastName = "Manning" Expect(u.FullName()).To(Equal("Peyton Manning")) }) }) Context("With only a first name", func() { It("should return the first name", func() { u.FirstName = "Peyton" Expect(u.FullName()).To(Equal("Peyton")) }) }) Context("With only a last name", func() { It("should return the last name", func() { u.LastName = "Manning" Expect(u.FullName()).To(Equal("Manning")) }) }) Context("When first and last name are missing", func() { It("should return the empty string", func() { Expect(u.FullName()).To(BeEmpty()) }) }) }) }) |

Yes, the tests are now less terse (in terms of number-of-lines) but nearly all the lines of code here are dedicated to one unified goal: expressively describing your code’s behavior. The Describe and Context blocks allow you to organize and document different scenarios; the BeforeEach blocks encapsulate and share repeated set-up code which allows you to write short, focused, It blocks to describe your code’s behavior. Finally, the Expect assertions provided by Gomega are descriptive one-liners that are easy to read – gone, for example, is the iferr!=nil{...} three-line stanza, replaced instead by the semantic Expect(err).NotTo(HaveOccurred()) Gomega matcher.

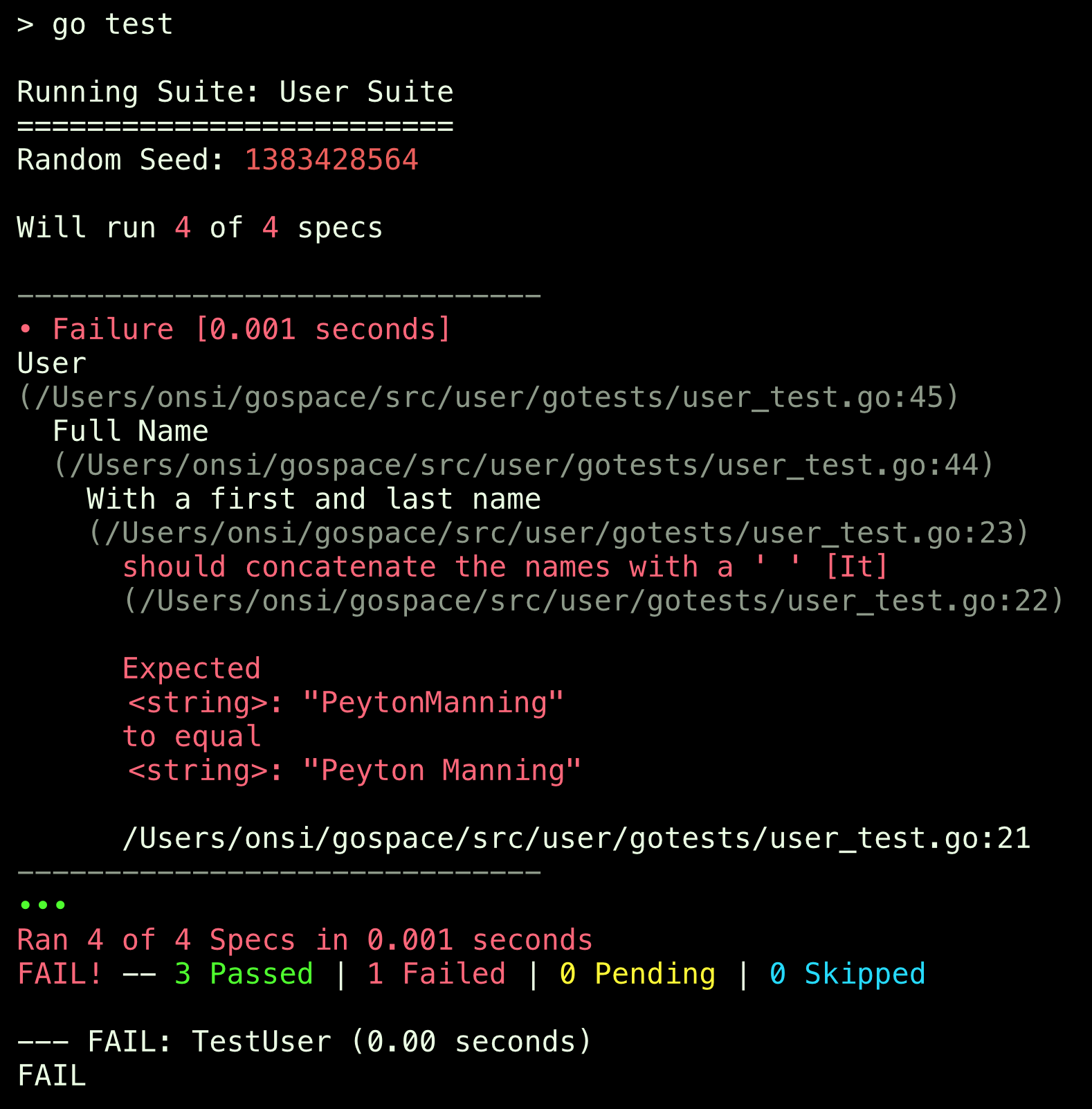

Of course, Ginkgo fits right into Go’s existing test infrastructure. You can run these tests using gotest` to get beautiful, descriptive, reporting:

Moreover, Ginkgo’s entry-point is just another XUnit style Test... function that can live alongside your existing XUnit tests making it possible to start migrating towards Ginkgo today. Here’s what a typical Ginkgo bootstrap looks like (you can generate this file using Ginkgo’s CLI - just run ginkgobootstrap`):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

package user_test import ( . "github.com/onsi/ginkgo" . "github.com/onsi/gomega" "testing" ) func TestUser(t *testing.T) { RegisterFailHandler(Fail) RunSpecs(t, "User Suite") } |

Finally, Ginkgo and Gomega are designed to complement Go’s strengths and mannerisms. Gomega has many matchers tailored specifically to Go’s particular semantics - for example you can Expect(myEmptyThing).To(BeZero()) and Expect(err).NotTo(HaveOccurred()). Both Ginkgo and Gomega have excellent support for asynchronous testing of concurrency-heavy code.

Agile developers spend a lot of time writing and grooming their test suites; Ginkgo and Gomega are geared towards improving your test-writing productivity in Go, helping you build and maintain test suites that eloquently describe your code’s behavior. Both packages have many more features than can be covered in a single blog post - all geared towards making your time writing tests in Go more pleasant and productive.

So Go forth and BDD!