Glow: Map Reduce for Golang

Having been a Java developer for many years, I have simply lost interest in Java and want to code everything in Go, mostly due to Go’s simplicity and performance. But it’s Java that is having fun in the party of big data. Go is sitting alone as a wall flower. There is no real map reduce system for Go, until now!

Glow is aiming to be a simple and scalable map reduce system, all in pure Go. Not only the system setup is simple and scalable, but also writing and running the map reduce code.

Glow also provides Map()/Filter()/Reduce() functions, which works well in standalone mode. It’s totally fine to just run in standalone mode. Let’s face it, very often you do not have that much data that has to run on a distributed system. Glow can fully utilize Go’s efficiency and goroutines to process fairly large amount of data. And if you really need to scale up, you can scale up with Glow by running it in distributed mode.

This time I will cover:

- Write a simple word count in standalone mode.

- Setup the distributed system.

- Run the word count in distributed mode.

- Process data on Hdfs and mongodb, and input and output data via Go channels.

People already read about Glow can skip to section 4 for a more realistic use case.

Boring Word Count

In distributed computing, the equivilent of hello word is a word count:

|

|

Here we load the “/etc/passwd” file and partitioned into 3 shards. Each shard is processed by 1 filter, 2 mappers, reduced to one count, and printed out via a mapper.

Let’s run this file:

1 2 |

$ go run t.go count: 532 |

I hope you like the code here. It may not look as simple as other languages that are skipping data types. But when a project gets reasonably large, readability is a big deal. Glow’s anonymous functions have the right amount of type information, which helps to understand the code, especially when someone else wrote it.

If you do not have much data now, you can actually stop here and run Glow in standalone mode. Glow’s API works for both standalone mode and distributed mode. I highly encourage you start using Glow in standalone mode. It should just work.

Go channels in Glow

Glow works natually with channels. The data flows from one dataset to the next dataset via channels, either in standalone mode or distributed mode.

Another interesting usage of channel is that a channel can be a mapper’s result emitter. Usually 1 mapper emits 1 result, which can be represented as function’s return result, e.g.,

|

|

func(line string, ch chan string) ```, it will be treated as the result emitter.

Setup Glow Cluster

Now let us setup the Glow cluster, just in case you need to scale up. Setting up Glow Cluster is super easy. First, build the “glow” binary file:

1

|

$ go get github.com/chrislusf/glow |

The compiled binary file is usually $GOPATH/bin/glow.

Now copy it to any computer, and run this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

// start a master on one computer > glow master // run one or more agents on computers > glow agent --dir ./glow/data --max.executors=16 --memory=2048 --master="localhost:8930" --port 8931 // it's fine to run several agents on the same computer > glow agent --dir ./glow/data2 --max.executors=8 --memory=512 --master="localhost:8930" --port 8932 |

Either master or agent only takes 5~6 MB memory. They are quiet and efficient. I highly recommend run this “glow agent” on any machine you can find, so that you can tap into the compute power any time you want, with one line of code change as follows.

Distributed Execution

Just insert this line to the import section, around line 7:

|

|

Now the word count can run distributedly this way:

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

$ go run t.go -glow 2015/12/08 00:54:46 localhost:8930 allocated 1 executors. 2015/12/08 00:54:46 localhost:8930 allocated 1 executors. 2015/12/08 00:54:46 localhost:8930 allocated 2 executors. 2015/12/08 00:54:46 localhost:8930 allocated 1 executors. 127.0.0.1:8931>count: 532 |

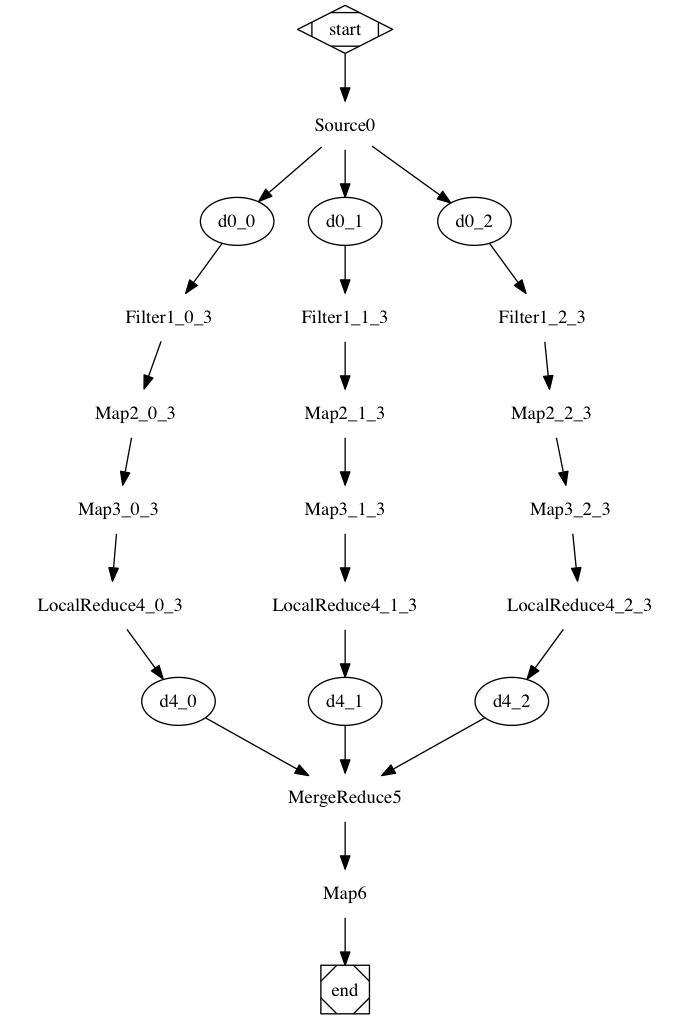

Also, you can visualize the flow. Run this command:

1 2 |

$ go run t.go -glow -glow.flow.plot > x.dot $ dot -Tpng -owc.png x.dot |

And the flow graph looks like this:

Something wrong!

You may get a different result when running distributedly vs standalone! This is because I cheated!

The input file “/etc/passwd” could be different on different servers. The file should be sent to the executor that’s running the TextFile() function. Let’s change the TextFile() call to this:

|

|

And make sure the file is shipped to the executor:

1 2 3 |

$ go run t.go -glow -glow.related.files="/etc/passwd" ... 127.0.0.1:8931>count: 532 |

As you can see, still many things can break when it comes to distributed mode. We need to understand how Glow works first.

Glow Underneath

How Glow works?

The word count code looks simple, but does many things. It can act as either a driver or an executor depending on command line parameters.

When the driver starts, it will ask the Glow master for resources. The master knows the system’s resource usage by the heartbeats from the Glow agents. The master will assign agents to the driver when available. By design, the Glow distributed system theorectically can run even with just one executor.

Then for each task, the driver would contact the assigned agents, and send a binary clone of itself, but run in executor mode. The driver will also tell the executor the input data locations.

Started by the agents, the executor will pull the data via network channels, process it, and write output to local agent.

The driver can send and receive data to the executors via network channels also.

Code structure

For many simple cases, the word count example is enough. However, in order to run the code as either driver or executor, this structure is recommended.

|

|

So basically 2 things to follow:

- the

flag.Parse()andflow.Ready()need to be called after the main() starts. - the flow definitions should be inside

init()

Why define flows in init()?

It is worth noting that I declared the flow definition in init() function.

This is because Go currently lacks the capability to dynamically compile and load a piece of code. This impacts the design of Glow. In distributed mode, Glow needs to send the compiled binary to Glow Agents, and then run the binary in executor mode by adding flow id and task id to existing command line options.

To achieve this correctly, the flows should be statically deterministic. The flows and the flow steps should not change given the same command line parameters.

Go’s init() is an ideal place to cleanly define flows, in one or multiple files.

How to make flows dynamically?

As mentioned above, the flows are static. How to dynamically change the flow?

Actually we do not change flows. We can just define multiple flows, and dynamically invoke a flow based on the results coming out of the flow via channels.

The flow definitions can be thought as machines. Your code can have many machines, defined in several files’ init() functions. Depending on your situation, you can start a machine, feed it via Go’s channels, and read the output also via Go’s channels.

A typical example would be running Linear Regression until the error is small enough. The error can be sent back to the driver, and the driver can decide whether it needs to run one more round of regression.

A more real example

Let’s assume you have a folder of log access files on hdfs, and want to join it with a Mongodb database of user accounts, to find out the most active user age group. The expected output is pairs of

|

|

go type LogLine struct { Page string UserId int } type UserAccount struct { UserId int Age int }

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

Go's strict type system is one of my favorite Go features. This would make refactoring super easy. When there are lots of data processing flows, detecting schema changes during compile time is invaluable. We will use Go's channels to feed data from the driver to the executors, and read the outputs out also via channels. However, the log files usually are fairly large. It's not efficient to read all data to the driver, and scatter them out to the cluster. Instead, we will just use the driver to list files under the folder, and send the list of files via channel to the executors. Each executor will pull its own input data from hdfs. This is [implemented in the ```hdfs.Source``` function] (https://github.com/chrislusf/glow/blob/master/source/hdfs/hdfs.go#L16). We will read the data from Mongodb from an executor. Here is the complete source code. |

go package main

import ( “flag” “fmt” “strconv” “strings”

_ “github.com/chrislusf/glow/driver” “github.com/chrislusf/glow/flow” “github.com/chrislusf/glow/source/hdfs” “labix.org/v2/mgo” )

type LogLine struct { Url string UserId int } type User struct { Id int Age int }

type AccessByAgeGroup struct { AgeRange int Count int }

var ( f = flow.New() flowOut = make(chan AccessByAgeGroup) )

func init() {

lines := hdfs.Source( // each executor reads a file from hdfs f, “hdfs://localhost:9000/etc”, 3, // listed files are partitioned to 3 shards ).Map(func(line string, ch chan LogLine) { parts := strings.Split(line, “,”) userId, _ := strconv.Atoi(parts[1]) ch <- LogLine{parts[0], userId} }).Map(func(line LogLine) (int, int) { return line.UserId, 1 }).ReduceByKey(func(a, b int) int { return a + b })

users := f.Source(func(out chan User) { // an executor reads from mongodb iterate(“mongodb://127.0.0.1”, “example”, “users”, func(iter *mgo.Iter) { var user User for iter.Next(&user) { out <- user } }, ) }, 3).Map(func(user User) (int, int) { return user.Id, user.Age / 10 })

lines.Join(users).Map(func(userId int, count int, ageRange int) (int, int) { return ageRange, count }).ReduceByKey(func(a, b int) int { return a + b }).AddOutput(flowOut) // the 2 ints fit into type AccessByAgeGroup

}

func main() { // needed to run on each executor flag.Parse() // needed to differentiate executor mode and driver mode. flow.Ready()

// just start the flow go f.Run()

// wait for the output for t := range flowOut { fmt.Printf(“age %d~%d, access count:%d\n”, t.AgeRange*10, (t.AgeRange+1)*10, t.Count) }

}

func iterate(mongodbUrl, dbName, collectionName string, fn func(*mgo.Iter)) { session, err := mgo.Dial(mongodbUrl) if err != nil { println(err) return } iter := session.DB(dbName).C(collectionName).Find(nil).Iter() fn(iter) if err := iter.Close(); err != nil { println(err) } }

1

|

Assume the file is x.go. Similarly, just run this in standalone mode: |

$ go run x.go

1

|

Run in distributed mode: |

$ go run x.go -glow

1

|

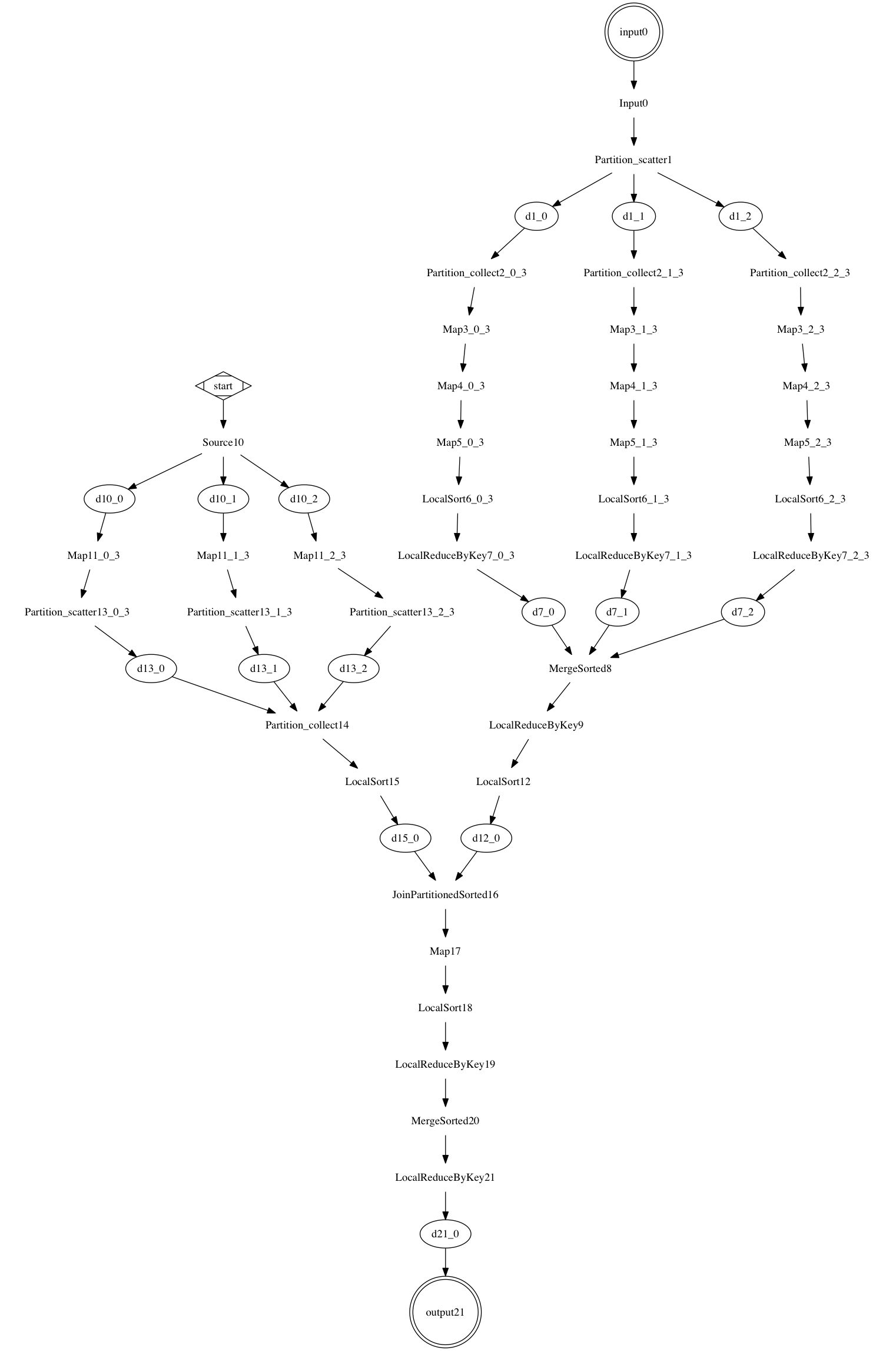

Generate the flow diagram: |

$ go run x.go -glow -glow.flow.plot > x.dot $ dot -Tpng -ojoin.png x.dot ```

The generated flow chart is:

Final words

Glow is simple, but powerful. Setting up a Glow cluster is super easy. A simple piece of code is all you need to run distributedly.

Conceptually, we just use Go’s channels to connect to a flow.

Glow has many components underneath. But the code is fairly easy to read, with potential to improve or customize. I welcome everyone to start using it and welcome any improvements.

Glow’s APIs, e.g., Map()/Reduce()/Filter() functions, can be used in standalone mode also. It makes code easy to read and write. This could also be quite useful.

Golang’s channel is an ideal model for moving data along the processing system. Glow currently works with batch proccesing, and may support stream processing in the future.

Glow also need to add monitoring, fault tolerant error handling, etc. Lots of work to be done. Welcome to any kind of contribution!

Glow has limitations that Go code can not be sent and executed remotely. My next project, Gleam, tries to address this. More details later.