Repeatable and Isolated Development Environments for Go

One of the common criticisms of the GOPATH is that it is hard to create isolated development environments without resorting to hacks, bash scripts, multiple GOPATH settings, or other trickery. Generally, I don’t often have too many problems with GOPATH, but when I do they are frustrating and hard to figure out. An example:

Your dependency manager copies deps from your GOPATH into your project’s vendor folder. But the dependency it copies is your fork, not the upstream, so the vendored package isn’t what you expected.

There are many ways to solve this problem, and the solutions depend greatly on your personal preferences for editing files. I’m going to outline my solution, which is interesting technically, but may not suit your workflow. I don’t claim to have tried all possible solutions, either, but I will outline some of the more interesting ones that I have tried.

Repeatable Environments

I’ve experimented for several years to make a simple, remote-friendly, repeatable development environment. One solution that stuck for longer than others was my dockerdevenv. It uses several layers of Docker filesystems plus a local filesystem bind to present a container that is isolated at the GOPATH level. It’s available via SSH or VNC. It was close, but VNC can be slow, and it still didn’t solve individual project isolation. I’ve also used Eclipse CHE and cloud9 – both hosted either locally or remotely – but was frustrated by the resource utilization of Che and cloud9’s pricing model.

None of these solutions felt quick or natural, though. I eventually bought an Intel NUC, loaded it up with RAM and a fast SSD, and installed Ubuntu. It became my headless development system, accessed via SSH. This solution works fairly well, especially if you’re comfortable with command-line editors like vim or emacs. It’s less fun if you want to use any UI for file editing, and the remote IP address means that any services/servers you start need to be exposed to listen on all interfaces rather than just binding to localhost, which is frequently the default.

LXD

One day I was stumbling through the Internet and I was reminded of LXD, a project from Ubuntu that adds some nice features on top of LXC. After working through a few of the tutorials, I realized that LXD had many features that made it appealing for my usecase.

- Like Docker, LXD/LXC use container technologies to isolate processes and network

- LXD is fast, stopping, starting, and creating containers is nearly instant if the image is present locally

- LXD allows you to create different

profilesand apply them to containers at or after creation time - Profiles can determine network configuration, privileges and more

An idea occurred to me: If I created a base container with my development tools setup, my dotfiles, etc. I could use LXD’s fast cloning to create a new container for every project, or for groups of projects! I experimented with this until I created a base container that was configured well for generic Go development. I named this container base.

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

bketelsen@arrakis:~$ lxc ls +-----------+---------+----------------------+------+------------+-----------+ | NAME | STATE | IPV4 | IPV6 | TYPE | SNAPSHOTS | +-----------+---------+----------------------+------+------------+-----------+ | base | STOPPED | | | PERSISTENT | 0 | +-----------+---------+----------------------+------+------------+-----------+ |

My thinking was that when I wanted to work on a new project, I’d use the clone functionality to clone the base container then start it and work in that container using lxc attach which is similar to docker exec. This worked, but the default LXD setup creates a network bridge (just like Docker does) that assigns containers their own IP addresses which aren’t routeable outside the host computer. It also meant that any services I would start in a container would have to be exposed using IPTables hackery, which I detest (because I’m not very good at it).

I did some more research and discovered that LXD supports several different networking models for the containers on a host. One of them is macvlan which makes the host’s network adapter appear to be multiple network adapters, each with a different MAC address on the host’s LAN interface. Containers that are started in this setup are peers to the host from a networking perspective, which means they’ll get IP addresses on your LAN rather than an unrouteable subnet like the bridge was assigning.

That’s really awesome!

It took a lot of searching and tweaking to figure out how to configure things, but I ended up with an addition to my default lxc profile that looks like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

bketelsen@arrakis:~$ lxc profile show default

<... snip ...>

devices:

eth0:

nictype: macvlan

parent: eno1

type: nic

<... snip ...> |

This configuration change causes containers started with the default profile to share the eno1 network adapter using macvlan and get IP addresses assigned from my router. I didn’t have to use any fancy ip link or bridge-utils tools to make it work, just changed the configuration and saved it. The next container I created got an IP address on my LAN! Because I had already enabled SSH services on the base container, I could SSH into the newly created container and clone a project and start working. very cool

An added bonus of the

macvlanapproach is that my router registers DHCP leases in DNS. LXD uses the container name as the DHCP host name. Therefore container “gopheracademy” becomes “gopheracademy.local” on my network. From any computer in my LAN I can typessh gopheracademyand it connects me to the container.

Remote Access

Since each container is a separate IP address on my LAN, I don’t have to do any crazy configuration on the host computer to proxy or forward traffic to the container. If I start a web server, I can access it inside the LAN at http://containername:port. This makes for really easy development. tmux means I can walk away and come back where I left off, too.

But if I’m not at home, it’s a little more complicated. I wanted to keep the same easy feeling for remote work, so I created high numbered port forwards for each of my most frequently used containers at my router. So if I’m away from home I can ssh to home.ip.address:52345 and get to the gopheracademy container via ssh. Install Fail2Ban and other security tools if you’re exposing anything on the interwebs, friends!

I also have a VPN connection I can use if I’m on a trusted computer which makes the experience the same as if I were developing locally. Since a VPN connection isn’t always possible, I like having the high-port SSH forwards as a backup.

GUI Access

Here’s where things get fun. Last week Amazon finally announced what they were doing with their cloud9 purchase. They’ve integrated it into the AWS console and enabled nice web-based development environments with EC2 backends. Cloud development with an Amazon twist. And an expensive one, if I were to create an environment for all the different projects I wanted to isolate. But reading the fine-print, the cloud9 development environments are free, and you ony pay for EC2 backend usage. BUT, you can skip the EC2 backend and connect your development environment to an SSH server.

I have some of those!

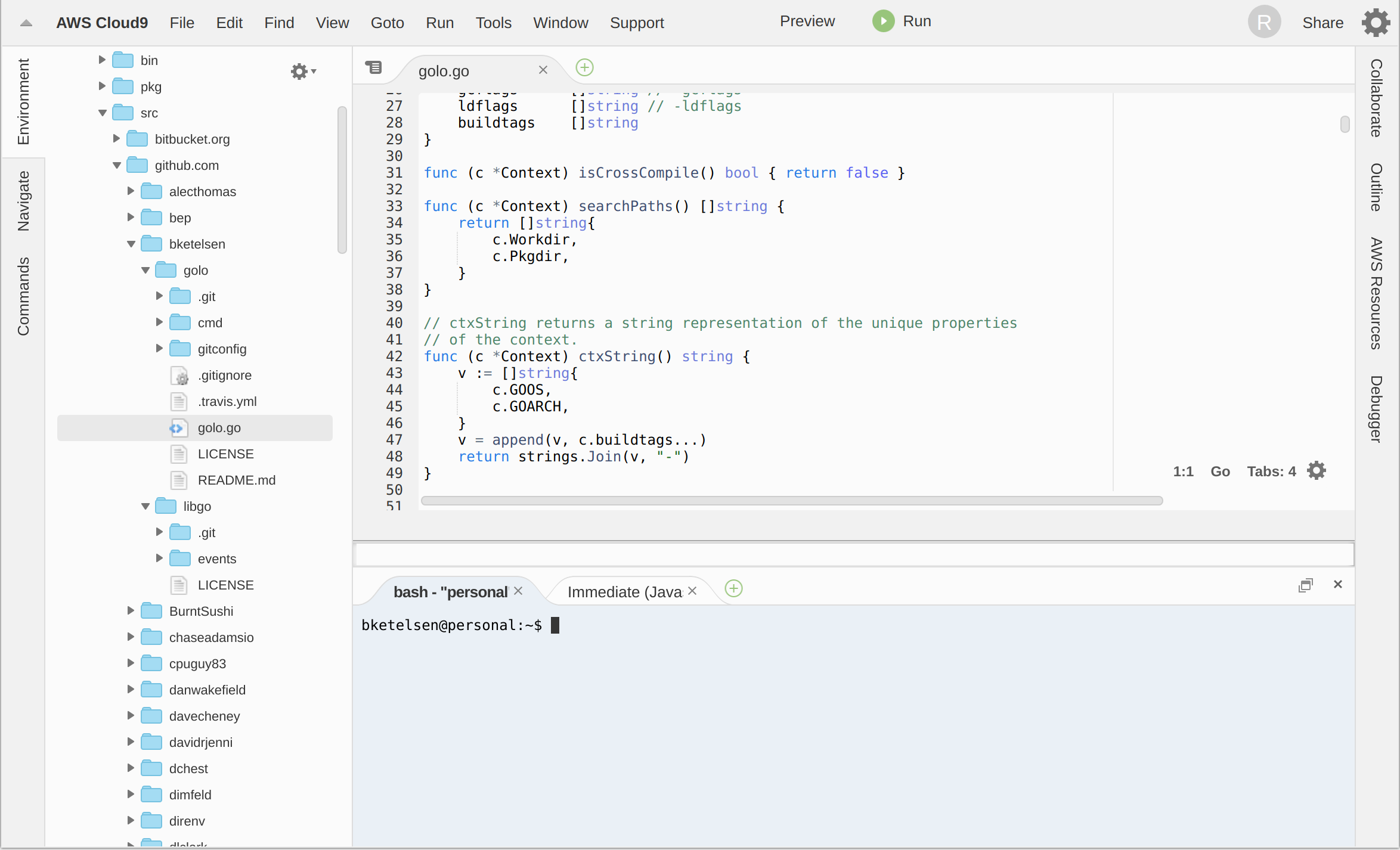

I tested it out by creating a cloud9 environment with SSH access through the high-port forwarding to one of my LXD containers. Not only did it work, but it was fast, comfortable, and pretty darn awesome.

An example workspace:

I setup workspaces and high-port forwards for all of my favorite projects, and now I can fall back to a browser based editor any time SSH/vim isn’t practical. And it’s free.

Automation

I couldn’t call myself a proper developer if I didn’t automate things a little bit, could I?

I created a bash script that automates all of this (except the port-forwarding, I’m too chicken to automate port-forwarding).

|

|

I called it newdev and execute like this:

|

|

It creates a clone of the base container named projectname and starts it. There is no Step 2.

Drawbacks

I’m still pretty new to LXD, so there may be some administration headaches I’m not aware of. One of the biggest pain points is that the LXD host and the containers can’t communicate over the network. This is due to something about macvlan. I tried to read and understand it, but my eyes glazed over and I stopped caring after the articles used terms like 802.11qr. It’s an easy limitation to deal with, because that host server is headless anyway. So I connect directly to the containers rather than going through the host. Which is what I wanted anyway. The limitation is most annoying when I want to move files from the host into the container. I know LXD allows shared/mounted directories in the containers from the host, so I may explore that if it gets annoying enough.

Repeatable and Isolated

Each development environment is repeatable, cloned from a base image. They’re 100% isolated too. It’s like having a Virtual Machine for each development environment without the overhead in CPU and disk space for many virtual machines. LXD has almost no overhead, and the containers use an overlay filesystem so the majority of the diskspace is shared with the base image.

I have local SSH and remote web access to my development containers, and I couldn’t be happier. I hope something in this post inspires you to tweak your development workflow and try new things, you just might find something new that makes your life easier.

Brian is a Cloud Developer Advocate at Microsoft. @bketelsen on twitter, https://brianketelsen.com on the web