Web Sessions and Common User Workflows - A Foundation for Go-Based Websites

Go is widely used to implement microservices and APIs. And for those wishing to set up a dynamic website without resorting to, say, Ruby or PHP, Go offers a lot of tools out of the box. The use of net/http and html/templates can get you very far already.

As soon as a user needs to be identified across multiple HTTP requests, you need to start thinking about web sessions. They can be thought of as storage units assigned to a user, which persist across requests. Some implementations store data in an encrypted cookie, others such as JSON Web Tokens (JWT) are often held in local browser storage.

The most common method is to store a token, or session ID, in a browser cookie. Based on that token, the server then loads the session data from a data store. Over the years, a number of best practices have evolved that make cookie-based web sessions reasonably safe. The OWASP organization lists a number of recommendations aimed at reducing common attacks such as session hijacking or session fixation. Unfortunately, many Go packages for web sessions leave it up to the user to implement these recommendations or don’t even provide the tools to do it.

Web Sessions

We present github.com/rivo/sessions, a Go package designed for cookie-based web sessions which implements OWASP recommendations. Its usage is quite simple:

|

|

Now you can already store data which will be available during subsequent HTTP requests:

|

|

The sessions package takes care of everything for you in the background: sessions expire after a period of inactivity, session tokens are regenerated regularly, and remote IP addresses as well as user agent strings are examined for unauthorized changes, leading to session invalidation. All of these options can be customized to your needs. Naturally, you can also connect any session store of your choice.

For many interactives websites, instead of saving data in the session directly, you may wish to step up one abstraction level and attach a User object to the session:

|

|

User is an interface so it imposes no specific structure on your existing user model (other than requiring a unique user ID). But help is provided with additional functions such as sessions.CUID(), a function that generates compact unique identifiers suitable for users, or sessions.ReasonablePassword() which implements NIST SP 800-63B guidelines for passwords.

Once you start implementing user account handling, you realize there are a lot of procedures that are common to most websites. In the interest of making these user accounts secure, it is probably not advisable to reinvent the wheel each time.

Common User Workflows

To facilitate the creation of websites with user accounts, we present github.com/rivo/users, a Go package which implements the following functions:

- User sign up and email verification

- Logging into a user account

- Logging out of a user account

- Checking if a user is logged in

- Forgotten password and password reset

- Email and password change

Like github.com/rivo/sessions, it is not a framework but rather a collection of tools you can integrate into your existing application. It is also somewhat opinionated, in that users are identified by their email addresses which no one else has access to. It therefore requires that you have access to an SMTP email server. If your application follows a different model, you will probably not be able to use this package out of the box. But it may still be a good start to implement your own user workflows.

The users package follows a number of rules:

- New user accounts or accounts whose email address was changed must be verified by clicking on a link sent per email.

- Authentication requires the user’s email and password.

- It must not be possible to find out if a specific email address belongs to an existing user account.

- Password strength is checked with

session.ReasonablePassword()(see above). - Forgotten passwords are reset by clicking on a temporary link emailed to the user.

- Users are in exactly one of three states: created, verified, and expired.

Using the package is very easy:

|

|

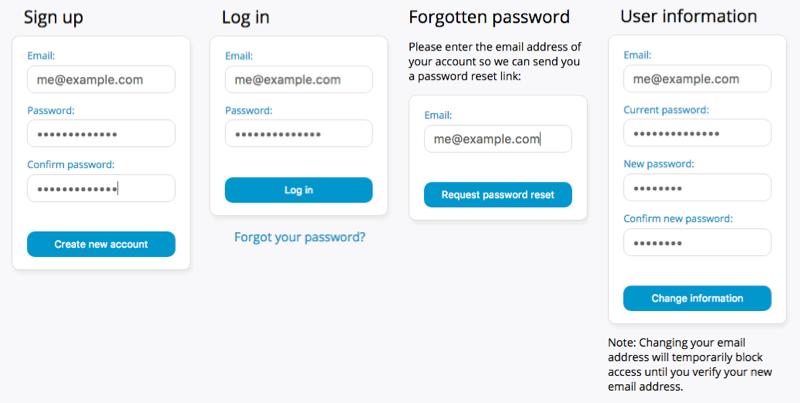

This will start an HTTP server with handlers for the pages listed above. You can add your own handlers to the http.DefaultServeMux before the call to users.Main(). The forms produced by those pages look like this (you will, however, need to provide your own CSS):

Alternatively, to start your own HTTP server, you can add all the package’s handlers yourself, simply by copying the implementation of the users.Main() function into your own code:

|

|

The package’s handlers use Golang templates to generate the HTML pages and the emails sent to the users. The HTML templates provided with the package contain the minimum HTML code to make the handlers work. When starting to work with this package, you will want to make a copy and adjusts the templates to the needs of your application. Support for internationalization is also included.

The users.Config variable holds a large number of configuration parameters allowing you to customize the package to your needs. You may choose any database for your user objects. (The default is a pure RAM store.) And just as in the github.com/rivo/sessions package, the User type is an interface with the functions needed by this package so you can bring your own user type.

Conclusion

If you are planning to implement a dynamic website using Go, the two packages github.com/rivo/sessions and github.com/rivo/users can save you a lot of time. The business logic of secure web sessions and common user workflows can be deceivingly complex. Our goal is to provide these functions without imposing an entire framework, so you can focus on your core application.

Of course, there are cases where these two packages may not be useful. For example, if you don’t use cookies to identify your sessions, most functions don’t apply. If your application runs on multiple servers, you may be able to use these packages with load balancers that implement sticky sessions but distributed sessions don’t come out of the box. And obviously, if your user model is very different from the model presented above, the users package may not help.

At the time of writing, both packages have just been released to the public. We would like to hear your feedback and if you encounter any problems or have suggestions, feel free to open issues on GitHub.