Contribute Beyond Code: Open Source for Everyone

Developers are often encouraged to contribute to open source. If you don’t consider yourself a developer, it can feel daunting to start on the journey to contributing. In the last year, I’ve found that the number of folks participating in open source is minimal in part to imposter syndrome associated with “but I’m not a developer”. In this article, I will share a little about why you should contribute to Go OSS projects, and provide some information about where to contribute, including some additional resources to get you started.

Why should you contribute to an open source project?

Participating in open source is a gift that keeps on giving. Everyone has their motivations, but some of the benefits of connecting with the community in an active role include:

- Promotes learning and development of skills. You can practice collaboration skills in roles that aren’t tied directly to performance reviews. You can develop other skills driven by your interests that are not part of your day job.

- Builds and promotes visibility. Your employer benefits from your participation in open source communities. You can find new job opportunities and potential co-workers.

What do you need?

First, figure out your employer’s policies for contributing to open source and review your employment agreement. While I think every company using open source software should give their employees time to contribute, often the contribution policies are problematic even if individuals contribute during personal time and on personal equipment. If your company doesn’t have a policy (or has a restrictive policy), sharing A Model IP and Open Source Contribution Policy may be helpful in providing guidance to improving the situation.

Specific software requirements will vary based on the project. Your skills in infrastructure as code or configuring continuous deployment pipelines may be extremely helpful to a project that hasn’t already implemented these practices. Your experience in these areas might drive the direction of software requirements; for example, a specific version of docker or cloud provider CLI.

If you’ve never done a pull request, the first-contributions project has a walkthrough as part of the repository. Every project will have a workflow and may have different recommendations on how to submit a pull request. It’s helpful to learn the fundamentals here rather than learning from scratch on a project of interest.

What kind of contributions?

Beyond developing features, areas of contribution can include:

- Reporting and replicating issues

- Mentoring

- Documentation (including writing blog posts for community events like the Gopher Academy Advent or liveblogging for GopherCon)

- Architecture diagrams

- CI/CD pipeline

- Infrastructure as code

- Separating secrets from code

- Maintaining tests

- Review pull requests

- Project management

- Supporting other community members

Many large projects have contributor summits that allow individuals to meet and collaborate in-person as well. For example, in these summits, providing a ops, design, project management, test, or security perspective can help guide the project to be more robust and resilient.

What project?

Sometimes, the best question to ask is who rather than what. Who do you want to collaborate with? Understanding the who can help guide your focus to specific projects that allow you to work with those folks.

Another question to ask yourself up front: How long do you want to contribute? For example, is this a one-time contribution, or something you are willing to provide on-going support? Being clear with your objectives can help you be successful in your selection of projects and contributions.

💡 Just because something is “public” on GitHub or Gitlab, and even if there are

CONTRIBUTINGfiles, it doesn’t mean that the repository owner wants collaborators or contributors. Sometimes folks are coding in the open. Before you invest a lot of work into a contribution, send an initial query through an issue or via a contact address.

It is often helpful to contribute to something that your company already depends on. This may help you fix something for the community at large that also helps you in your day job (and doesn’t require you maintaining a separate fork forever!).

You can also explore things that aren’t related to your company at all! This will help you to learn about other areas that can help you grow your skills and filter future job opportunities.

Strategies for identifying projects

One method to find projects is to look for active projects in your skill sets. I’m going to walk through finding a Go project.

💡 Communities may have a specific artifact repository that can help you identify popular projects. Chef Supermarket, Puppet Forge, Go Packages,RubyGems can help you find Chef, Puppet, Go, and Ruby projects for example.

Lots of Go projects are on GitHub. Searching for go, and then limiting the Languages to Go specifically will give me a sorted list of projects based on “Best Match”.

“Best Match” generally isn’t super helpful for exploring projects to support with contributions. I can modify my sort options, for example to “Most stars” to find the buzz factor of a project, or “Recently updated” to find fresh projects.

“Recently updated” is an interesting sort factor to find all kinds of obscure projects that might not get noticed otherwise. It also will have any projects that folks might be coding in the open where they are working with go, so that can be distracting.

Choosing “Most stars” will start with huge projects like go, kubernetes, and moby. These projects will have a significant amount of governance and processes to understand prior to contributing. These are great projects to contribute to, but the processes would be much longer than a blog post to describe the evaluation process.

💡 To contribute to the Go project directly, the Go contributing guidelines provide some insight into code contributions but not as much for other non-code contributions. As a really large project, there are a number of folks and processes in place. If you are new to contributing to Open Source, I wouldn’t suggest jumping in there with non-code contributions without direct support from active folks already contributing in that community.

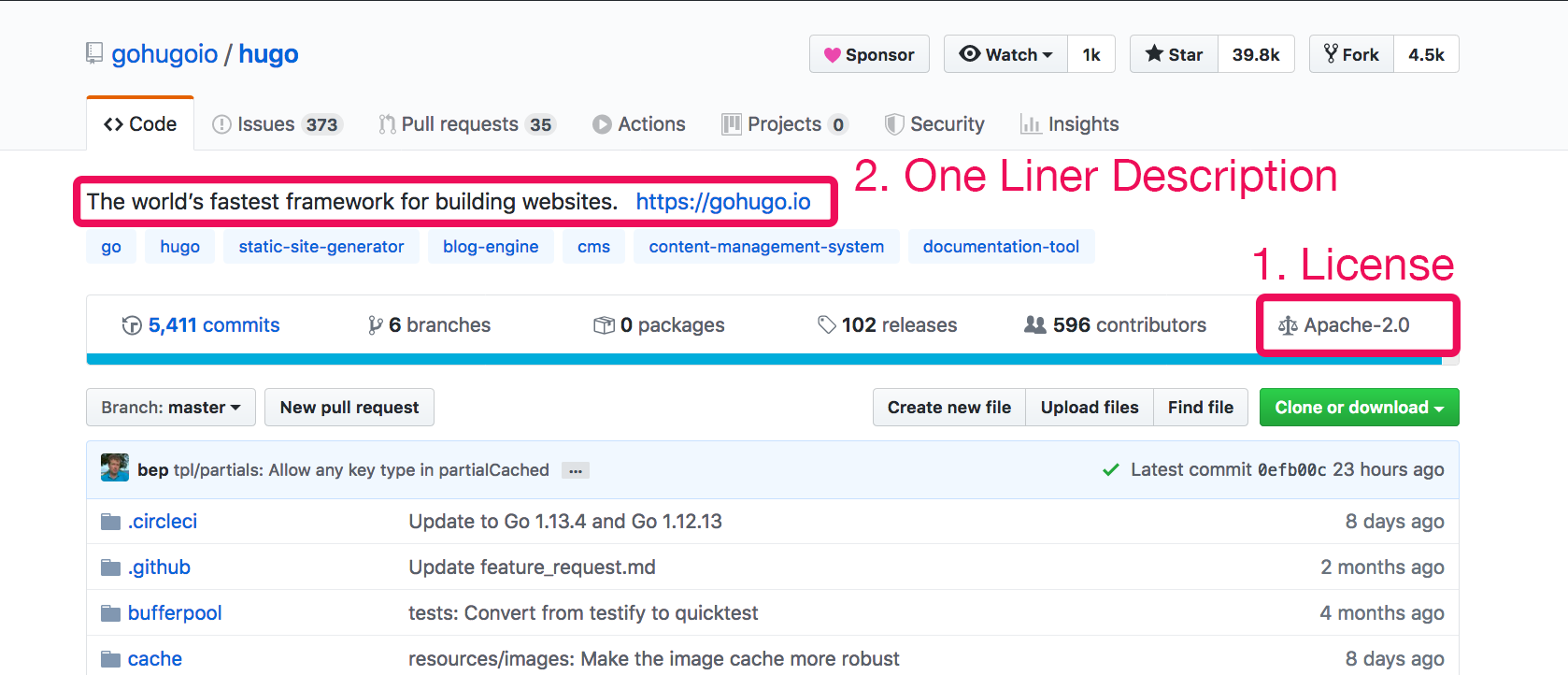

The Hugo project is a little bit further down and looks like a great project that is slightly smaller but still has a lot of support and impact.

One of the first things I do when evaluating a project is to verify that the project is properly licensed for open source. Just because something is on GitHub doesn’t mean that it’s available to use, modify or share. If it doesn’t have an explicit license that allows for using, modifying, and sharing, then it’s a non-starter for contributions.

💡 The Open Source Initiative maintains the list of open source licenses that comply with the Open Source Definition. Licenses that are included in this list allow software to be freely used, modified, and shared.

The hugo project has an Apache-2.0 License so it’s good for contributions.

Next, I look at the one liner for the GitHub repo listed at the top of the project. For Hugo, it’s “The world’s fastest framework for building websites.” and includes a link to the website.

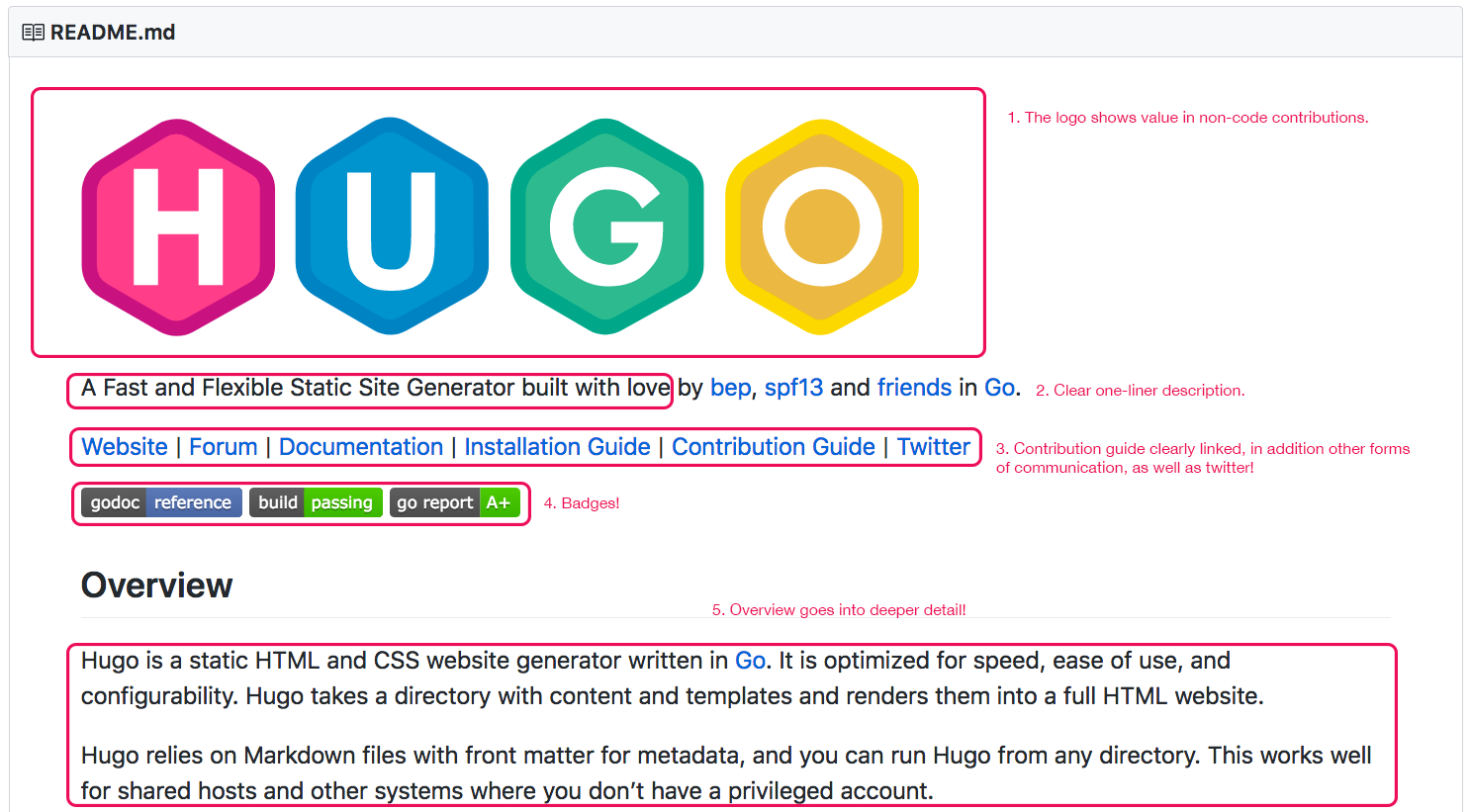

For GitHub projects, the README.md is shown below the main file directory of the project. The top few lines are helpful at a quick glance for additional information about the project.

A logo for a project shows that there is some amount of investment into the project beyond just code. The one liner here is more clear about what this project is “A Fast and Flexible Static Site Generator built with love”. Finally, there is a set of badges that help provide clarity about the state of the projects and answers potential questions:

- does it have CI? build

- do they value documentation? godoc

- do they lint and follow recommended practices? go report

I then check whether the project has explicit contributing guidelines defined in a README.md or CONTRIBUTING.md.

The first great sign I see is that the Hugo project explicitly shares a number of different type of non-code contributions that they value including a link to the hugoDocs project.

If I don’t know what I could contribute to the project, and need to know what would be a strategic investment of my time to help others, I could check the open unclaimed issues.

I also look at the number of contributors on the project; I will still support a project that only has a few contributors, but it does give me insight into how overloaded they might be (especially if the project is popular).

Overall, when I look at the Hugo project a lot is going for it:

- It’s currently active, i.e. has regular contributions from a lot of different people.

- The

READMEis current with a quality one liner description of the project, supported documentation, and steps to install for binary and from source. - The

CONTRIBUTINGdocumentation is detailed with links to the hugoDocs project, support questions, reporting issues, and PR process. - There is a more detailed contributing guide on the website.

- There is a “Proposal” label that shows that the team welcomes input from the community.

- I know from external sources, that Hugo is an immensely popular tool for building out static websites so the impact of contribution is large.

From here, there are a number of directions I could go. If I was interested in doing a one off contribution, for example maybe I discovered some weirdness between behaviors of a specific version of Hugo I was using for my website and documentation. I could spin up the latest version and see if I can replicate it in latest. If it still is a problem in latest, I could submit an issue describing the problem, and a PR to update documentation.

If I was looking to do bigger contributions, I could ask on one of the issues labeled “Proposals” whether it’s “ok for me to pick this up”, and collaborate with maintainers. I could work with maintainers to improve the process for testing and document it within the contributing guidelines.

A different method for identifying projects within a specific skill set is to look at broader community opportunities. These will vary and be specific to that particular project. These can be harder to find because often community opportunities require being aware of the groups doing work within the community. Some avenues for discovering these include:

- GopherCon is one example of a great Go community event with a broad base of support with the contributor summit, workshops, and wide range of talks.

- Go events is a list of world-wide Go meetups.

- Gophers slack is the Go community slack.

Another method to find a project to contribute to is to look at aggregating platforms for insight into available projects. Many of these are organized from a developer perspective. For example, CodeTriage provides a list of popular projects on GitHub, sorted by language. Mozilla provides a more nuanced “choose your adventure” process that helps you drill down to a possible project to get involved with.

A final method is to look for community inquiries. These can come via different channels the Gophers slack or Twitter, for example.

- Carolyn Van Slyck put out a call for Porter contributors on Twitter in September of 2019. Porter has a welcoming website that states the project values and guidelines upfront and lists the steps to take to get started contributing.

- In December of 2019 on Twitter, Aaron Schesinger shared a call for support for Athens on Azure Kubernetes Service with a more detailed blog post describing in broad strokes the plan.

Identify possible contributions

Some projects use labels to mark issues that are good for new contributors. These issues generally focus on documentation or code issues but are good way to learn about the project as a beginner. It’s helpful to lurk and examine both open and closed issues to see how contributors participate and maintainers support contributions.

💡 Be kind in your contributions. If you find that your chosen project has toxicity that makes contributing negative, it’s OK to walk away from the project and find something new. Toxicity can look and feel different to each contributor.

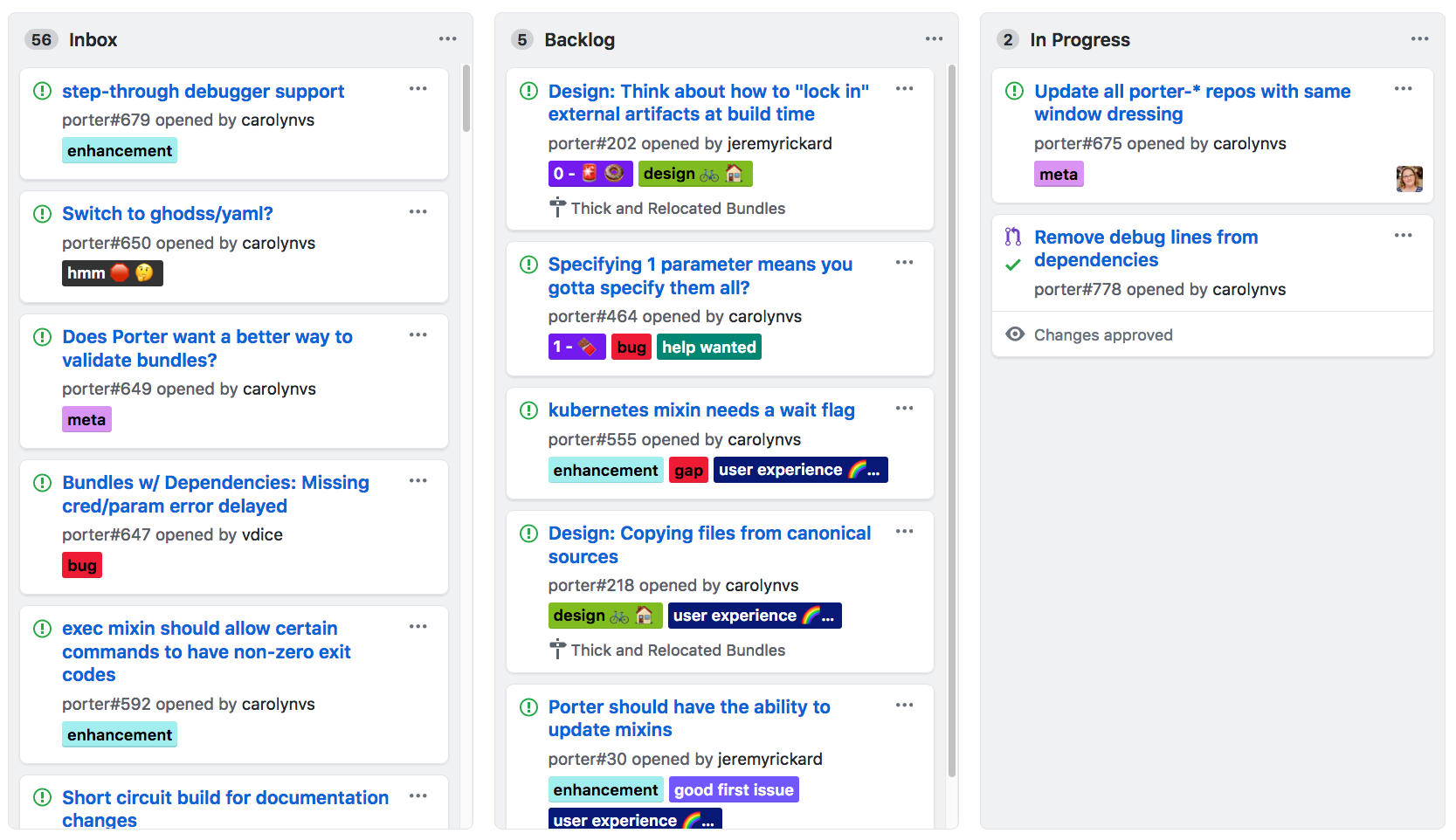

Sometimes projects will use Trello or GitHub Projects to organize planned issues. Larger projects may have a regular scheduled online community hangout to plan and identify areas of concern.

Here is an example of the Porter project project and prioritized tasks using a GitHub Project board:

The Porter project has a rich set of labels from this prioritized view to see “good first issue” tasks as well as more specific classification of issues.

Wrap Up

While many of the resources out there focus on developers, we all have a lot to contribute to go projects in open source. We don’t have to accept software as-is. We can shape, define, and help move industry practices in our desired directions.

If you want to have a greater impact and support open source as a whole, join the Open Source Initiative, a member-driven community non-profit that promotes the use of open source software.

If you want to learn more about contributing to open source, read Forge Your Future with Open Source by VM Brasseur.

I’d love to hear about your open source contributions (especially the ones that aren’t visible because they aren’t PRs). Share in the comments or with #OSSandTell on Twitter.

Thank you to

- Dan Maher for editing the original version of this article for Sysadvent.

- Aaron Schlesinger for his invaluable time in the Go project walkthrough, as well as early feedback for this article.

- Carolyn Van Slyck for quality project maintership that encourages contribution.

Additional Resources:

- A Model IP and Open Source Contribution Policy

- Forge Your Future with Open Source by VM Brasseur

- Check whether a license is a valid Open Source Licenses

- Join the Open Source Initiative

- Open Source Guides and the project

About the Author

Jennifer Davis is an experienced systems engineer, speaker, and author. Her books include Effective Devops, Collaborating in DevOps Culture, and the upcoming Modern System Administration. She advocates for the community at Microsoft. Reach out via twitter at @sigje, dev.to/sigje, or visit her website.