Plumbing and Semantics: Communication Patterns in Distributed System

Introduction

In distributed systems, multiple components running on different machines—physical or virtual—communicate and coordinate to accomplish tasks.

Distributed systems building typically focuses on the way components communicate. As things change (e.g. infrastructure, configuration, components), pressures arise and must be accommodated. Most of you have heard of loose coupling, which asserts that communications between components should be as flexible and adaptive as possible.

Why is this a design goal? The more rigidly a system is coupled together, the more likely it’ll break down and fail to adapt to change.

Loose coupling is applicable in two main areas: plumbing and semantics. Plumbing is the addressing, discovery, and connectivity between components. Never hard code the IP and port for a communication component within another component’s source code. If that machine were to fail and move, it would assume a new IP and port.

For sustainable loose coupling, use a configuration file, change it, and run the component again after the information changes. Well known services like DNS locate and connect components and services.

What if you needed components within a system to scale independently? More than one for a certain component class? This is horizontal scale. Load balancers and proxies help solve the problem and components talk through these intermediaries. DNS can also return multiple entries, and Anycast is also applicable.

What about service-level agreements (SLAs)? How do you maintain high SLAs in fast-changing environments?

Plumbing and Semantics

Plumbing and semantics. Plumbing connects a cell phone call and tunes to your favorite radio station. Semantics are languages people speak to communicate over the phone or radio. Distributed systems usually characterize this by a message payload. These days, many new plumbing and semantics architectures use HTTP for the plumbing and JSON for the semantics, or the “payload”. Both HTTP and JSON are well supported in modern languages and toolkits.

Today, I often use HTTP and JSON in distributed systems. I’ve spent 20+ years designing, building, and utilizing Publish/Subscribe Messaging Systems. They remain a core architectural pattern of any distributed system I design and are used for addressing, discovery, and a flexible control plane. I typically use JSON for the semantics, regardless of whether the plumbing is HTTP or a messaging system.

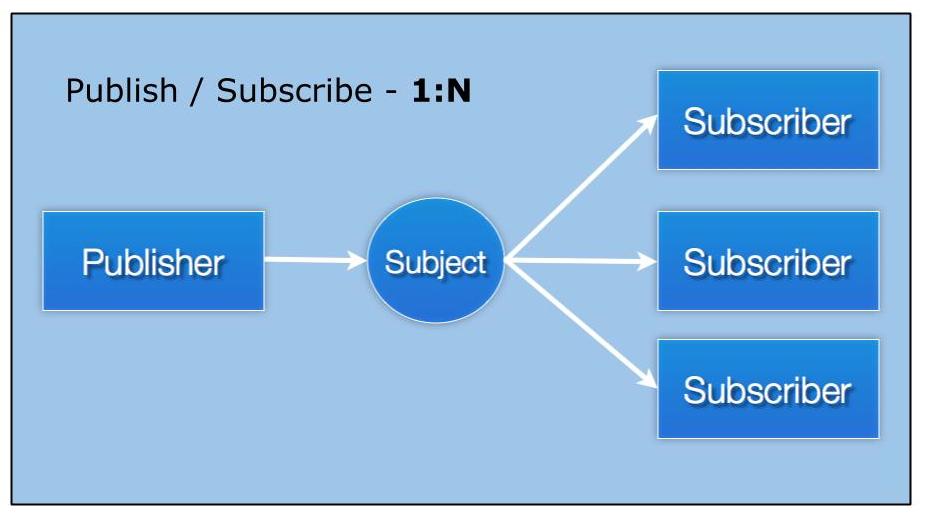

Within a basic Publish/Subscribe System, messages are sent to topics or subjects, and that—rather than IP sets and ports—upholds addressing in the system. Subjects connect Senders and Receivers. Note that all subscribers matching the subject will receive the message. Simply adding a new subscriber to the system allows multiple recipients to receive a message without further configuration changes.

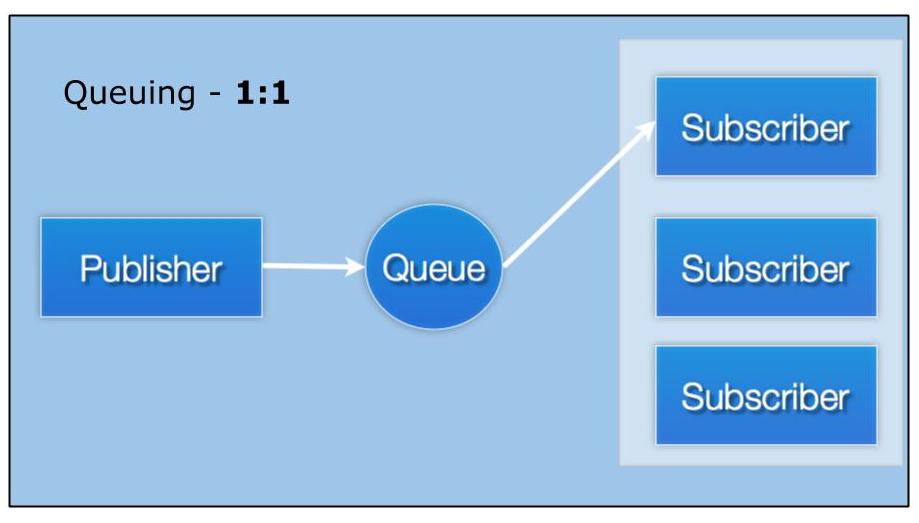

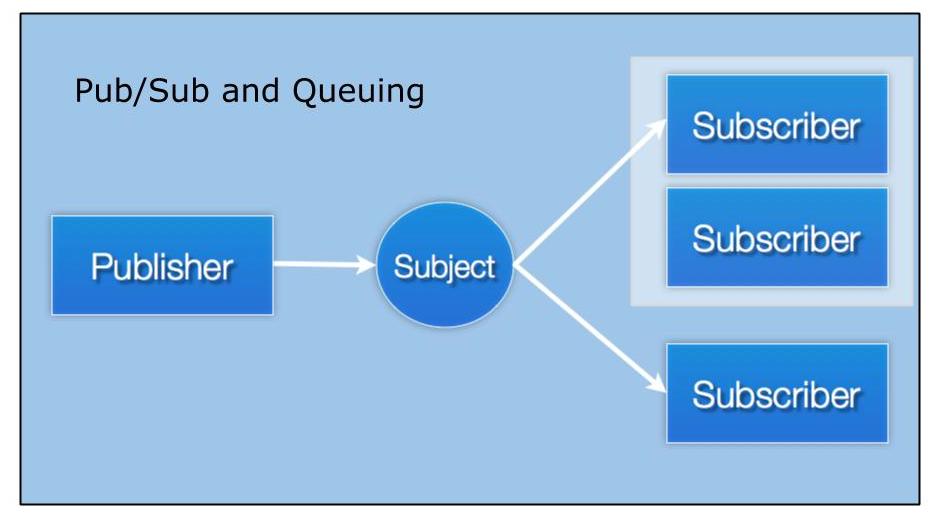

Many messaging systems also use queueing, a pattern where multiple subscribers exist, but only one receives any given message. I believe that a messaging system should provide the way to have many queue groups in a distributed fashion, and that they should be able to co-exist with normal publish-subscribe operations.

I believe queueing is an interest-based operation, not a sending operation found in many popular queueing products. An interest operation, or something that a subscriber does, enables both normal publish/subscribe and queueing patterns to co-exist in the same subject space and process messages accordingly from a single publisher. This has important implications. A group of subscribers forming a queue group can horizontally scale and reduce overall response time to inbound queries. If queueing were a publish operation, it’d be difficult to add other subscribers or an additional queue group of subscribers to achieve system functionalities such as logging, analytics, or audit trails.

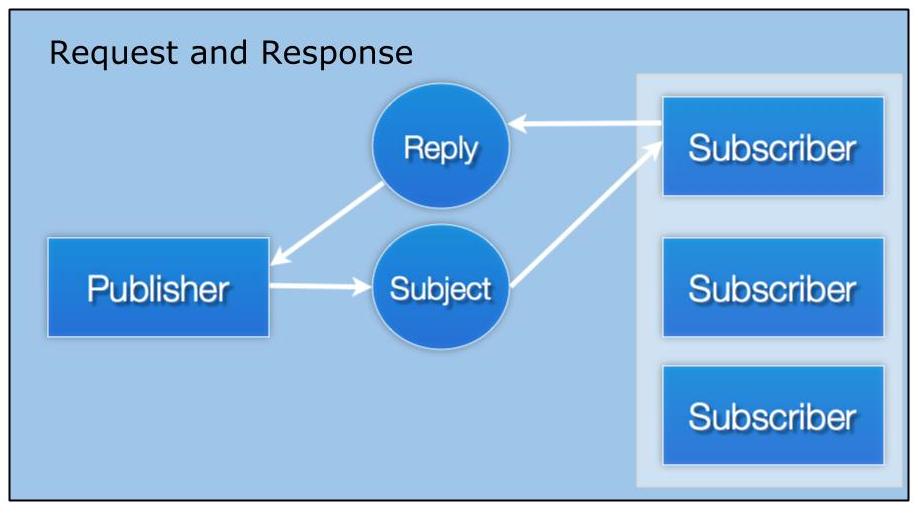

Request/response overlays both publish/subscribe and distributed queueing patterns. A requestor sends a request and receives one or more responses. Again, all connected via subjects, so that requestors and responders move and scale at will without configuring changes and updates. Loose coupling at its finest.

NATS and the associated high-performance server are an open source messaging system built to satisfy these patterns. Unlike traditional messaging systems, it does not have persistence, transactions, or any type of guaranteed delivery models. In my opinion, these were never needed by the industry (though I built quite a few of them), and actually led to bad distributed system design. Think of NATS as a nervous system that simply fires and forgets and presents an ever-present dial tone service that protects itself at all costs. I introduce NATS to provide context for the following examples.

Here’s an applicable example that illustrates the power of these patterns:

Google search is always fast, returning results instantly. Speed has always been a Google mantra. (Disclaimer: I worked at Google from 2003-2009.) How does it work? Google divides widespread information into different buckets or shards. Your request goes to all shards that answer the question based on what they know, then the answers are collected, ordered, delivered to you. Since speed reigns, shards are replicated, all replicas get the request and answer at (about) the same time, and the fastest one back wins. Get the answer to the user as fast as possible!

Example

While not reproducing Google search, we will use similar patterns to achieve a speedy result. A simple adder adds multiple integers together. We can use more adders to represent “shards”, but I leave that as an exercise for you. We replicate the adder classes and identify them with IDs that they generate on startup. Requests will be sent to all replicas, which respond with both the answer and ID of the responders so we see who “wins”.

Below is the main loop for the example which can be found on Github.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 |

// Flags

var numResponders int

var numRequests int

flag.IntVar(&numResponders, "numResponders", DefaultResponders, "Responders to spin up.")

flag.IntVar(&numRequests, "numRequests", DefaultRequests, "Requests to send.")

flag.Parse()

// Start the NATS server.

startNatsServer()

// Spin up the appropriate number of responders.

fmt.Printf("\nSpinning up %d responders.\n\n", numResponders)

for i := 0; i < numResponders; i++ {

adder.NewAdder(ReqSub)

}

// Grab a client connection for sending requests.

nc := adder.NatsConn()

// Time to wait for a response before timing out.

ttl := 10 * time.Millisecond

var req *adder.Request

var resp adder.Response

// Send some requests.

fmt.Printf("\nSending %d requests.\n\n", numRequests)

for i := 0; i < numRequests; i++ {

req = &adder.Request{X: rand.Int63() % 100, Y: rand.Int63() % 100}

nc.Request(ReqSub, req, &resp, ttl)

fmt.Printf("Request: %+v\tResponse: %+v\n", *req, resp)

}

fmt.Printf("\nFinished\n\n") |

Interest Graph Pruning

If there are many possible responders, the requestor could face CPU spikes as the client library discards responses 2-N. NATS proactively prunes interest graphs on the fly. Concretely, this means that NATS understands that the client desires one response to the request and therefore prunes the subscription (and hence the interest) after the first response is sent to the client. This alleviates CPU load on the client, and allows the requestor pattern to operate efficiently at scale.

Summary

Modern communication patterns in distributed systems enable speed, scalability, adaptability, and optionality. Many such patterns exist, and we have only touched upon a few in this article. Many projects utilize messaging as a foundation in their systems, such as OpenStack, Baidu, Cloud Foundry, and Continuum by Apcera.

Please feel free to contact me on Twitter, Github, or by e-mail if you have any questions.