Recursion and Tail Calls in Go

Introduction

This guest post is written by William Kennedy, author of the Going Go blog.

I was looking at a code sample that showed a recursive function in Go and the writer was very quick to state how Go does not optimize for recursion, even if tail calls are explicit. I had no idea what a tail call was and I really wanted to understand what he meant by Go was not optimized for recursion. I didn’t know recursion could be optimized.

For those who don’t know what recursion is, put simply, it is when a function calls itself. Why would we ever write a function that would call itself? Recursion is great for algorithms that perform operations on data that can benefit from using a stack, FILO (First In Last Out). It can be faster than using loops and can make your code much simpler.

Performing math operations where the result of a calculation is used in the next calculation is a classic example where recursion shines. As with all recursion, you must have an anchor that eventually causes the function to stop calling itself and return. If not, you have an endless loop that eventually will cause a panic because you will run out of memory.

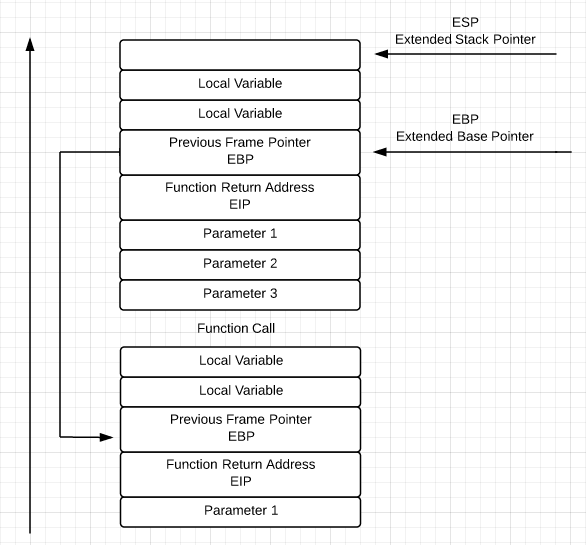

Why would you run out of memory? In a traditional C program, stack memory is used to handle all the coming and going of function calls. The stack is pre-allocated memory and very fast to use. Look at the following diagram:

This diagram depicts an example of a typical program stack and what it may look like for any program we write. As you can see the stack in growing with each function call we make. Every time we call a function from another function, variables, registers and data is pushed to the stack and it grows.

In a C program each thread is allocated with its own fixed amount of stack space. The default stack size can range from 1 Meg to 8 Meg depending on the architecture. You have the ability to change the default as well. If you are writing a program that spawns a very large number of threads, you can very quickly start eating up a ton of memory that you probably will never use.

In a Go program each Go routine is allocated its own stack space. However, Go is smarted about allocating space for the routines stack. The stack for a Go routine starts out at 4k and grows as needed. The ability of Go to be able to grow the stack dynamically comes from the concept of split stacks. To learn more about split stacks and how they work with the gcc compiler read this:

You can always look at the code implemented for the Go runtime as well:

When we use recursion we need to be aware that the stack is going to grow until we finally hit our anchor and begin to shrink the stack back down. When we say that Go does not optimize for recursion, we are talking about the fact that Go does not attempt to look at our recursive functions and find ways to minimize stack growth. This is where tail calls come in.

Before we talk more about tail calls and how they can help optimize recursive functions, let’s begin with a simple recursive function:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 |

func Recursive(number int) int {

if number == 1 {

return number

}

return number + Recursive(number-1)

}

func main() {

answer := Recursive(4)

fmt.Printf("Recursive: %d\n", answer)

} |

This Recursive function takes an integer as a parameter and returns an integer. If the value of the number variable is one, then the function returns the value out. This if statement contains the anchor and starts the process of unwinding the stack to complete the work.

When the value of the number variable is not the number one, a recursive call is made. The function decrements the number variable by one and uses that value as the parameter for the next function call. With each function call the stack grows. Once the anchor is hit, each recursive call begins to return until we get back to main.

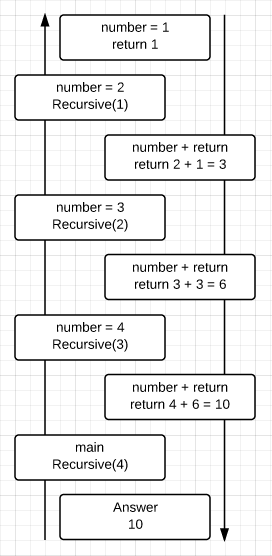

Let’s look at a view of all the function calls and return values for the program:

Starting from the left side and from bottom to top we can see the call chain for the program.

Main calls Recursive with a value of 4. Then Recursive calls itself with a value of 3. This continues to happen until the value of 1 is passed into the Recursive function call.

The function calls itself 3 times before it reaches the anchor. By the time the anchor is reached, there are 3 extended stack frames, one for each call.

Then the recursion begins to unwind and the real work begins. On the right side and from top to bottom we can see the unwind operations.

Each return operation is now executed by taking the parameter and adding it to the return value from the function call.

Eventually the last return is executed and we have the final answer which is 10.

The function performs this operation very quickly and it is one of the benefits of recursion. We don’t need any iterators or index counters for looping. The stack stores the result of each operation and returns it to the previous call. Again, the only drawback is we need to be careful of how much memory we are consuming.

What is a tail call and how can it help optimize recursive functions? Constructing a recursive function with a tail call tries to gain the benefits of recursion without the drawbacks of consuming large amounts of stack memory.

Here is the same recursive function implemented with a tail call:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

func TailRecursive(number int, product int) int {

product = product + number

if number == 1 {

return product

}

return TailRecursive(number-1, product)

}

func main() {

answer := TailRecursive(4, 0)

fmt.Printf("Recursive: %d\n", answer)

} |

Can you see the difference in the implementation? It has to do with how we are using the stack and calculating the result. In this implementation the anchor produces the final result. We don’t require any return values from the stack except the final return value by the anchor which contains the answer.

Some compilers are able to see this nuance and change the underlying assembly that is produced to use one stack frame for all the recursive calls. The Go compiler is not able to detect this nuance yet. To prove that let’s look at the assembly code that is produced by the Go compiler for both these functions.

To produce a file with the assembly code, run this command from a Terminal session:

1

|

go tool 6g -S ./main.go > assembly.asm |

There are three compilers depending on your machine architecture.

6g: AMD64 Architecture: This is for modern 64 bit processors regardless if the processor is built by Intel or AMD. AMD developed the 64 bit extension to the x86 architecture.

8g: x86 Architecture: This is for 32 bit processors based on the 8086 architecture.

5g: ARM Architecture: This is for RISC based processors which stands for Reduced Instruction Set Computing.

To learn more about this and other go tool commands look at this page:

I listed the Go code and the assembly code together. Just one item of note to help you.

In order for the processor to be able to perform an operation on data, such as adding or comparing two numbers, the data must exist in one of the processor registers. Think of registers as processor variables.

When you look at the assembly below it helps to know that AX and BX are general purpose registers and used all the time. The SP register is the stack pointer and the FP register is the frame pointer, which also has to do with the stack.

Now let’s look at the code:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 |

07 func Recursive(number int) int {

08

09 if number == 1 {

10

11 return number

12 }

13

14 return number + Recursive(number-1)

15 }

--- prog list "Recursive" ---

0000 (./main.go:7) TEXT Recursive+0(SB),$16-16

0001 (./main.go:7) MOVQ number+0(FP),AX

0002 (./main.go:7) LOCALS ,$0

0003 (./main.go:7) TYPE number+0(FP){int},$8

0004 (./main.go:7) TYPE ~anon1+8(FP){int},$8

0005 (./main.go:9) CMPQ AX,$1

0006 (./main.go:9) JNE ,9

0007 (./main.go:11) MOVQ AX,~anon1+8(FP)

0008 (./main.go:11) RET ,

0009 (./main.go:14) MOVQ AX,BX

0010 (./main.go:14) DECQ ,BX

0011 (./main.go:14) MOVQ BX,(SP)

0012 (./main.go:14) CALL ,Recursive+0(SB)

0013 (./main.go:14) MOVQ 8(SP),AX

0014 (./main.go:14) MOVQ number+0(FP),BX

0015 (./main.go:14) ADDQ AX,BX

0016 (./main.go:14) MOVQ BX,~anon1+8(FP)

0017 (./main.go:14) RET , |

If we follow along with the assembly code you can see all the places the stack is touched:

0001: The AX register is given the value from the stack that was passed in for the number variable.

0005-0006: The value of the number variable is compared with the number 1. If they are not equal, then the code jumps to line 14 in the Go code.

0007-0008: The anchor is hit and the value of the number variable is copied onto the stack and the function returns.

0009-0010: The number variable is subtracted by one.

0011-0012: The value of the number variable is pushed onto to the stack and the recursive function call is performed.

0013-0015: The function returns. The return value is popped from the stack and placed in the AX register. Then the value for the number variable is copied from the stack frame and placed in the BX register. Finally they are added together.

0016-0017: The result of the add is copied onto the stack and the function returns.

What the assembly code shows is that we have the recursive call being made and that values are being pushed and popped from the stack as expected. The stack is growing and then being unwound.

Now let’s generate the assembly code for the recursive function that contains the tail call and see if the Go compiler optimizes anything.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 |

17 func TailRecursive(number int, product int) int {

18

19 product = product + number

20

21 if number == 1 {

22

23 return product

24 }

25

26 return TailRecursive(number-1, product)

27 }

--- prog list "TailRecursive" ---

0018 (./main.go:17) TEXT TailRecursive+0(SB),$24-24

0019 (./main.go:17) MOVQ number+0(FP),CX

0020 (./main.go:17) LOCALS ,$0

0021 (./main.go:17) TYPE number+0(FP){int},$8

0022 (./main.go:17) TYPE product+8(FP){int},$8

0023 (./main.go:17) TYPE ~anon2+16(FP){int},$8

0024 (./main.go:19) MOVQ product+8(FP),AX

0025 (./main.go:19) ADDQ CX,AX

0026 (./main.go:21) CMPQ CX,$1

0027 (./main.go:21) JNE ,30

0028 (./main.go:23) MOVQ AX,~anon2+16(FP)

0029 (./main.go:23) RET ,

0030 (./main.go:26) MOVQ CX,BX

0031 (./main.go:26) DECQ ,BX

0032 (./main.go:26) MOVQ BX,(SP)

0033 (./main.go:26) MOVQ AX,8(SP)

0034 (./main.go:26) CALL ,TailRecursive+0(SB)

0035 (./main.go:26) MOVQ 16(SP),BX

0036 (./main.go:26) MOVQ BX,~anon2+16(FP)

0037 (./main.go:26) RET , |

There is a bit more assembly code with the TailRecursive function. However the result is very much the same. In fact, from a performance perspective we have made things a bit worse.

Nothing has been optimized for the tail call we implemented. We still have all the same stack manipulation and recursive calls being made. So I guess it is true that Go currently does not optimize for recursion. This does not mean we shouldn’t use recursion, just be aware of all the things we learned.

If you have a problem that could best be solved by recursion but are afraid of blowing out memory, you can always use a channel. Mind you this will be significantly slower but it will work.

Here is how you could implement the Recursive function using channels:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

func RecursiveChannel(number int, product int, result chan int) {

product = product + number

if number == 1 {

result <- product

return

}

go RecursiveChannel(number-1, product, result)

}

func main() {

result := make(chan int)

RecursiveChannel(4, 0, result)

answer := <-result

fmt.Printf("Recursive: %d\n", answer)

} |

It follows along with the tail call implementation. Once the anchor is hit it contains the final answer and the answer is placed into the channel. Instead of making a recursive call, we spawn a Go routine providing the same state we were pushing onto the stack in the tail call example.

The one difference is we pass an unbuffered channel to the Go routine. Only the anchor writes data to the channel and returns without spawning another Go routine.

In main an unbuffered channel is created and the RecursiveChannel function is called with the initial parameters and the channel. The function returns immediately but main does not terminate. This is because it waits for data to be written to the channel. Once the anchor is hit and writes the answer to the channel, main wakes up with the result and it is printed to the screen. In most cases main will wake before the Go routine terminates.

Recursion is another tool you can use when writing your Go programs. For now the Go compiler will not optimize the code for tail calls but there is nothing stopping future version of Go from doing so. If memory could be a problem you can always you a channel to minic recursion.