Writing a Distributed Systems Library in Go

Writing a Distributed Systems Library in Go

Introduction

In early 2013, I needed to add distributed processing and storage to my open source behavioral analytics database. To my surprise, there were almost no libraries for distributing data. Tools like doozerd were great for building systems on top of but I didn’t want my database to depend on a third party server.

As I began to read distributed systems research papers I began to understand why there were not many libraries available. The research papers that I found described distributed systems protocols in abstract, mathematical formulas so making the jump to building a concrete implementation was a huge hurdle.

Fortunately, a Stanford paper was published in April 2013 on the Raft distributed consensus protocol. One of the design goals of Raft was to be understandable and, for me, this was immediately evident. I was able to understand the paper and how it related to my application so I began work on what would become the go-raft library.

Most people will never need to write their own implementation of distributed consensus, however, I found that writing go-raft was a great learning experience so I’d like to share some of the lessons I learned.

Quick Overview of Raft & Distributed Consensus

There are numerous talks (1, 2, 3), slides (1, 2) and articles (1, 2) about how Raft works so I won’t get into detail about it here but I do want to give a quick overview.

The basic premise of Raft is that you have a cluster of servers which maintain a consistent view of your data by sharing an ordered log of commands. When these commands are replayed, each server ends up with the same data. This is all done safely so that consistency can be maintained even in the face of server or network failures.

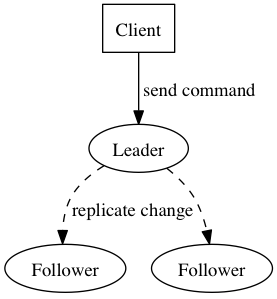

The library also maintains a current leader that can accept new commands from clients. The leader replicates these commands to other servers in the cluster (i.e. “peer” servers) and the leader decides when it is safe to execute the commands. The leader maintains its leadership by periodically sending out heartbeat messages to its peers.

Server nodes can be in one of three states at any given time: “follower”, “candidate”, or “leader”.

Lesson #1: Sequential Execution, FTW!

In the original version of go-raft, I heavily used the sync package so the library could thread safe. However, trying to manage locks as the library grew became more and more difficult. It wasn’t uncommon to run into race conditions and deadlocks during early testing of the library.

Using locks also made it incredibly difficult to reason about the flow of data. In go-raft we use a Server object to manage the local state and log. This Server needs to simultaneously accept new commands from clients while also providing state information for peers. Server methods could be called in any order and it was hard to reason about how the server state transitioned between method calls.

The best decision I made while writing go-raft was to refactor it to use an event loop. Instead of allowing clients to modify the server at any time, all changes are funneled through a single go channel. The server’s event loop pulls the next client request off the channel and all changes are executed within a single thread. The client is then notified through a separate channel when the request is fully committed to the cluster. This simple architectural change had a huge effect on the stability of the library and the ease of development.

Making your code execution sequential also has the added benefit that it is easily testable. Any parts of your library that have multiple threads can operate nondeterministically which can turn into a testing nightmare.

Lesson #2: Nondeterministic Testing

Because we’re dealing with multiple servers running our application concurrently, we’re dealing with a nondeterministic system by definition. Servers can crash, messages can be lost, and thread schedulers can pause so we need to account for these issues in our library. This means we need to write tests to simulate these different scenarios.

The Raft protocol depends on the wall clock to maintain “liveness” so we need to account for it in our tests. In general, I’ve found Go’s time.Sleep() to be fairly reliable on my local machine down to the millisecond. However, on hosted CI environments such as Travis CI I’ve seen much larger swings so it can be useful to bump up these sleep delays significantly.

Another more reliable option is to build event dispatch into your library. With go-raft, the EventDispatcher sends out many different types of events such as “state change” and “leader change”. Attaching a listener in your unit test and waiting for an event can help avoid wall clock issues entirely.

Lesson #3: Limit Your Exposure

Writing distributed systems is hard. With so many moving parts it’s difficult to reason about how the system works. A big part of the job of our library is to _isolate_our_distributed_systems_problem_to_one_place_in_ourcode.

With go-raft we try to accomplish this by providing a simple setup and simple command interface. The raftd reference implementation project is a good place to see a full working example but let’s look at the basics of using go-raft right here.

Let’s look at a quick example of a distributed calculator. The full, runnable

example of this code can be found at this Github repo.

First we’ll setup our main() function to initialize our server, create a single

currentValue variable to hold our application state, and an /add endpoint

so we can add a new number:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 |

package main import ( ... "github.com/goraft/raft" ) var server raft.Server var currentValue int func main() { hostname, _ := os.Hostname() // Initialize the internal Raft server. transporter := raft.NewHTTPTransporter("/raft") server, _ = raft.NewServer(hostname, ".", transporter, nil, nil, "") // Attach the Raft server to the HTTP server to transport Raft messages. transporter.Install(server, http.DefaultServeMux) // Create a /add endpoint. http.HandleFunc("/add", addHandler) // Start servers. server.Start() log.Fatal(http.ListenAndServe(":8000", nil)) } // addHandler executes a command against the raft server and returns the result. func addHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, req *http.Request) { value, _ := strconv.Atoi(req.FormValue("value")) newValue, err := server.Do(&AddCommand{Value: value}) if err != nil { http.Error(w, err.Error(), http.StatusInternalServerError) return } fmt.Fprintf(w, "%d\n", newValue) } |

From here the only API you need to worry about is Server.Do() method which

accepts an object implementing the Command interface. This interface simply

includes the CommandName() function and the Apply() function. The command

name is a way to associate the type with an entry in the log. This handles

serialization of commands automatically.

The Apply function is simply a function that changes your application state

in some way. In our example, we’ll just have an AddCommand:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

func init() {

raft.RegisterCommand(&AddCommand{})

}

// AddCommand adds a number to the current value of the system.

type AddCommand struct {

Value int

}

func (c *AddCommand) CommandName() string {

return "add"

}

func (c *AddCommand) Apply(ctx raft.Context) (interface{}, error) {

currentValue += c.Value

return currentValue, nil

} |

When the AddCommand is executed, it will automatically distribute the command

to other members in the cluster and safely commit before the Do() command

returns. This command interface lets us completely abstract away the details of

leader election and log replication so you can just focus on writing your

application logic.

For more detail on how to setup cluster configuration and other details of go-raft, please checkout the raftd reference implementation.

How to Apply These Lessons

Since the Raft paper came out there has been an explosion of new implementations in a variety of languages. As we all begin to understand the fundamental components of distributed systems better I hope that more types of libraries become available. With more and more complex architectures being developed these core libraries are becoming increasingly important.

I hope these lessons I presented here help you to better understand the difficulties of distributed systems libraries but I also hope it inspires some of you to create and share your own implementations. When I started with go-raft I was not a newcomer to the distributed systems world but I’ve learned so much in the past year. There’s never a better way to learn than to roll up your sleeves and dig in.

Please feel free to hit me up on Twitter, Github, or by e-mail if you have any questions.

[ Editor’s Note – This is the first article in our January series on Distributed Computing in Go. If you have got a topic to contribute shoot us a note : social@gopheracademy.com ]