Go Advent Day 3 - Building a Twelve Factor App in Go

Introduction

I’ve been writing a lot of Go code lately, but only recently discovered the Twelve Factor App manifesto. Coming from an Operations background I really resonated with many of the topics and solutions covered by Twelve Factor. If you have not read the manifesto go check it out, I’ll wait…

It’s pretty obvious there are twelve things you gotta do to build a Twelve Factor App, but in this post I’m going to focus on factor three, which mandates that application configuration be stored in the environment. The reasons for storing configuration in the environment are outlined in the manifesto, but no longer having to manage app configuration files has me sold.

Application Configuration

Before moving on we need to define application configuration:

“An app’s config is everything that is likely to vary between deploys (staging, production, developer environments, etc).”

For most applications configuration includes logging levels, port bindings, and database settings. These settings are typically stored in configuration files, for example:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

# /etc/myapp.conf debug = true host = db.example.com password = password port = 80 timeout = 30 username = myapp |

Following the third factor we must forgo configuration files and instead store our configuration settings using environment variables. On my Linux system I can easily set configuration values from the command line by exporting them.

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

export MYAPP_DEBUG="true" export MYAPP_HOST="db.example.com" export MYAPP_PASSWORD="password" export MYAPP_PORT="80" export MYAPP_TIMEOUT="10" export MYAPP_USERNAME="myapp" |

Notice the use of the MYAPP prefix. Though not required, using a prefix is common practice and helps prevent namespace collisions. Once set I can read configuration values from the command line like this:

1 2 |

$ echo $MYAPP_DEBUG true |

It’s equally as easy to access environment variables in Go using the os package:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

package main import ( "fmt" "log" "os" "strconv" ) var debug bool func main() { raw_debug := os.Getenv("MYAPP_DEBUG") debug, err := strconv.ParseBool(raw_debug) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } fmt.Printf("Debug is set to: %v\n", debug) } |

The biggest drawback to storing configuration in the environment is that you can only store string values; it’s up to you to convert these strings into values that can be used by your application. While Go makes this task pretty straightforward I would like to avoid this kind of boilerplate.

That’s where envconfig comes in.

Introducing envconfig

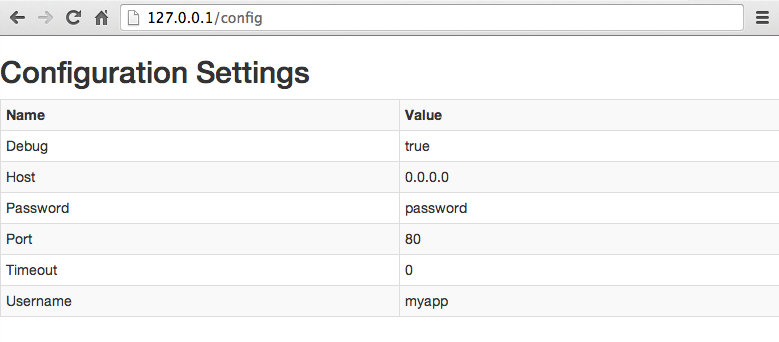

envconfig is a simple Go library designed to process a specification and extract configuration from the environment. The following example will create a simple web application which displays its configuration settings on the /config end-point.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 |

package main import ( "fmt" "html/template" "log" "net" "net/http" "github.com/kelseyhightower/envconfig" ) var configHTML = `<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta charset="utf-8"> <title>MyApp Config</title> <link href="//netdna.bootstrapcdn.com/bootstrap/3.0.2/css/bootstrap.min.css" rel="stylesheet"> </head> <body> <h2>Configuration Settings</h2> <table class="table table-bordered table-striped table-condensed"> <tr><th>Name</th><th>Value</th></tr> <tr><td>Debug</td><td>{{ .Debug }}</td></tr> <tr><td>Host</td><td>{{ .Host }}</td></tr> <tr><td>Password</td><td>{{ .Password }}</td></tr> <tr><td>Port</td><td>{{ .Port }}</td></tr> <tr><td>Timeout</td><td>{{ .Timeout }}</td></tr> <tr><td>Username</td><td>{{ .Username }}</td></tr> </table> </body> </html>` // Spec represents the myapp configuration. type Spec struct { Debug bool Host string Password string Port string Timeout uint Username string } // spec holds the myapp configuration. var spec Spec func ConfServer(w http.ResponseWriter, req *http.Request) { t := template.New("configHTML") t.Parse(configHTML) t.Execute(w, spec) } func main() { err := envconfig.Process("myapp", &spec) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } http.HandleFunc("/config", ConfServer) listenAddr := net.JoinHostPort(spec.Host, spec.Port) if err = http.ListenAndServe(listenAddr, nil); err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } } |

The most import bit happens on the following line:

1

|

err := envconfig.Process("myapp", &spec) |

The configuration will be populated by the envconfig.Process() function. This is done by looking up environment variables based on capitalized struct file names prefixed with the prefix string; i.e MYAPP_USERNAME.

If you have Go setup on your system, you can save the above example to myapp.go under your local GOPATH directory. For example:

1 2 3 |

$ mkdir -p $GOPATH/src/github.com/kelseyhightower/myapp $ cd $GOPATH/src/github.com/kelseyhightower/myapp $ vim myapp.go |

Next fetch the envconfig dependency and build the myapp binary:

1 2 |

$ go get $ go build |

At this point we are ready to configure and launch the myapp application. All we have to do is export a few environment variables:

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

export MYAPP_DEBUG="true" export MYAPP_HOST="0.0.0.0" export MYAPP_PASSWORD="password" export MYAPP_PORT="80" export MYAPP_TIMEOUT="10" export MYAPP_USERNAME="myapp" |

Then start the myapp application

1

|

$ ./myapp |

You should now be able to visit http://127.0.0.1/config and see a table listing myapp’s configuration settings.

How does envconfig work?

Behind the scenes envconfig makes use of Go’s reflect and strconv packages. Let’s walk through a section of the envconfig source code that’s responsible for extracting configuration from the environment and converting the results to the appropriate type.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

package main import ( "fmt" "log" "os" "strconv" ) var debug bool func main() { raw_debug := os.Getenv("MYAPP_DEBUG") debug, err := strconv.ParseBool(raw_debug) if err != nil { log.Fatal(err) } fmt.Printf("Debug is set to: %v\n", debug) } |

First step is to ensure the specification is a struct.

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

s := reflect.ValueOf(spec).Elem()

if s.Kind() != reflect.Struct {

return ErrInvalidSpecification

}

typeOfSpec := s.Type() |

Next we iterate over each struct field in the specification, and if settable, meaning we can assign a value to it, we start the following process:

- Combine the prefix, an underscore character, and the struct field name to form the configuration key.

- Capitalize the configuration key and lookup its value in the environment.

for i := 0; i < s.NumField(); i++ { f := s.Field(i) if f.CanSet() { fieldName := typeOfSpec.Field(i).Name key := fmt.Sprintf(“%s_%s”, prefix, fieldName) value := os.Getenv(strings.ToUpper(key))

1 2 3 |

if value == "" {

continue

} |

Next envconfig converts the string retrieved from the environment to a value with the same type as the struct field represented by f.Kind() and assigns the value to the struct field represented by f.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 |

switch f.Kind() {

case reflect.String:

f.SetString(value)

case reflect.Int, reflect.Int8, reflect.Int16, reflect.Int32, reflect.Int64:

intValue, err := strconv.ParseInt(value, 0, f.Type().Bits())

if err != nil {

return &ParseError{

FieldName: fieldName,

TypeName: f.Kind().String(),

Value: value,

}

}

f.SetInt(intValue)

} |

Notice for the string type we can simply assign whatever we get from the environment, but for other types we have to do a little more work.

Conclusion

Hopefully this post has highlighted some benefits of Twelve Factor applications; specifically how leveraging the environment for application configuration can provide a nice alternative to config files and make your apps more portable. But more importantly this post demonstrates how Go’s powerful language features not only support building Twelve Factor Apps, but makes it almost trivial to do so.