Go and Apache Arrow: building blocks for data science

Today we will see how Apache Arrow could be useful for data science, or – really – a lot of analysis workloads.

Lingua franca

In Data Science and in many scientific fields, the lingua franca is Python.

This means that a lot of the libraries are written in Python, with the CPU intensive parts leveraging either NumPy, SciPy or, directly, a C/C++ library wrapped with the CPython C-API. This also means that:

- the vast majority of the analysis pipelines are written in Python;

- it is not completely straightforward to migrate parts of these pipelines to other languages, in a smooth and piecewise process.

So why would anyone use Go for this?

Well… the usual reasons:

- Go is easier to deploy,

- Go is faster than pure Python,

- Go code is simpler when dealing with concurrency,

- Go code and results are easy to reproduce,

- Go code is more amenable to mechanical refactoring,

- Go code tends to be more robust at scale than Python code.

The real question is: do we have all the building blocks, all the libraries to write a modern, robust, efficient analysis pipeline in Go?

Most of the science-y things one might carry out with the Python scientific stack (NumPy/SciPy) can be performed with Gonum:

- linear algebra, matrices,

- differentiation,

- statistics, probability distributions,

- integration, optimization,

- network creation,

- Fourier transformations,

- plots.

There are also a few packages that enable file-level interoperability with many useful data science oriented or scientific “file formats”:

Many basic ingredients are already there, even if some are still missing.

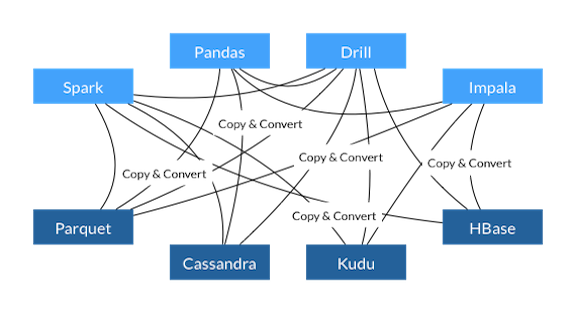

But even if basic file-level interoperability is (somewhat) achieved, one still needs to implement readers, writers and converters from one file format to any another when integrating with a new analysis pipeline:

In many scenarios, this implies a large fraction of the computation is wasted on serialization and deserialization, reimplementing over and over the same features for converting from format-1 to format-n or from format-1 to format-m, etc…

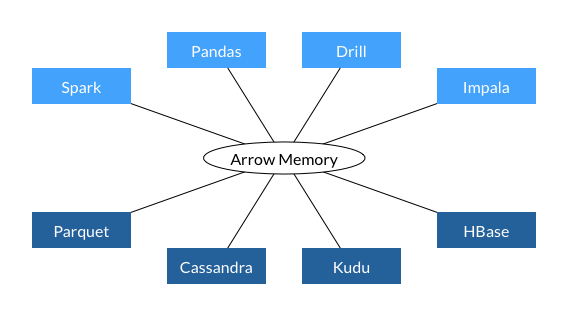

What if we had a common data layer between all these analysis pipelines, a common tool that would also be efficient?

Apache Arrow

What is Apache Arrow? From the website:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

Apache Arrow is a cross-language development platform for in-memory data. It specifies a standardized language-independent columnar memory format for flat and hierarchical data, organized for efficient analytic operations on modern hardware. It also provides computational libraries and zero-copy streaming messaging and interprocess communication. |

The idea behind Arrow is to describe and implement a cross-language open standard for representing structured data, and for efficiently sharing this data across languages and processes.

This is embodied as an arrow::Array class in C++, and the Vector class in Java, the reference implementations.

Languages currently supported include C, C++, Java, JavaScript, R, Ruby, Rust, MATLAB and Python.

… and – of course – Go :)

InfluxData contributed the original Go code for Apache Arrow, as announced here. The Go Arrow package (started by Stuart Carnie) had support for:

- primitive arrays (

{u,}int{8,16,32,64},float{32,64}, …) - parametric types (

timestamp) - memory management

- typed metadata

- SIMD math kernels (via a nice automatic translation tool -

c2goasm- to extract vectorized code produced by CLang, see the original blog post for more details)

Since then, a few contributors provided implementations for:

- list arrays

- struct arrays

- time arrays

- loading

CSVdata to Arrow arrays, - tables and records,

- tensors (a.k.a. n-dimensional arrays), the Swiss Army knife of machine learning.

Note that tensors are not part of the columnar format: they are actually built on top of Arrow arrays.

But what are those arrays?

Arrow arrays

From the Arrow perspective, an array is a sequence of values with known length, all having the same type.

Arrow arrays have support for “missing” values, or null slots in the array.

The number of null slots is stored in a bitmap, itself stored as part of the array.

Arrays with no null slot can choose not to allocate that bitmap.

Let us consider an array of int32s to make things more concrete:

1

|

[1, null, 2, 4, 8] |

Such an array would look like:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

* Length: 5, Null count: 1 * Null bitmap buffer: |Byte 0 (validity bitmap) | Bytes 1-63 | |-------------------------|-----------------------| | 00011101 | 0 (padding) | * Value Buffer: |Bytes 0-3 | 4-7 | 8-11 | 12-15 | 16-19 | 20-63 | |----------|-------------|-------|-------|-------|-------------| | 1 | unspecified | 2 | 4 | 8 | unspecified | |

Arrow specifies the expected memory layout of arrays in a document.

How does it look like in Go? The Go implementation for the Apache Arrow standard is documented here:

- github.com/apache/arrow/go/arrow: data types, metadata, schemas, …

- github.com/apache/arrow/go/arrow/array: array types,

- github.com/apache/arrow/go/arrow/memory: support for low-level allocation of memory,

- github.com/apache/arrow/go/arrow/csv: support for reading CSV files into Arrow arrays,

- github.com/apache/arrow/go/arrow/tensor: types for n-dimensional arrays.

The main entry point is the array.Interface:

|

|

Most of the interface should be self-explanatory.

The careful reader might notice the Retain/Release methods that are used to manage the memory used by arrays.

Gophers might be surprised by this kind of low-level memory management, but this is needed to allow for mmap- or GPU-backed arrays.

Another interesting piece of this interface is the Data() method that returns a value of type *array.Data:

|

|

The array.Data type is where all the semantics of an Arrow arrays are encoded, as per the Arrow specifications.

The last piece to understand the memory layout of a Go Arrow array is memory.Buffer:

|

|

In a nutshell, Arrow arrays – and the array.Interface – can be seen as the cousins of the buffer protocol from Python which has been instrumental in (pythonic) science.

Let us come back to the int32 array.

It is implemented like so in Go:

|

|

Creating a new array value holding int32s is done with array.NewInt32Data(data) where data holds a carefully crafted array.Data value with the needed memory buffers and sub-buffers (for the null bitmap.)

As this can be a bit unwiedly, a helper type is provided to create Arrow arrays from scratch:

|

|

Arrow arrays can also be sub-sliced:

|

|

Similar code can be written for arrays of float64, float32, unsigned integers, etc…

But not everything can be mapped or simply expressed in terms of these basic primitives.

What if we need a more detailed data type?

That is expressed with Lists or Structs.

Let us imagine we need to represent an array of “Person” type like:

|

|

Handling nested data and finding an efficient representation for this kind data are key features of the Apache Arrow project. Minute details of this efficient representation are reported in the memory layout document.

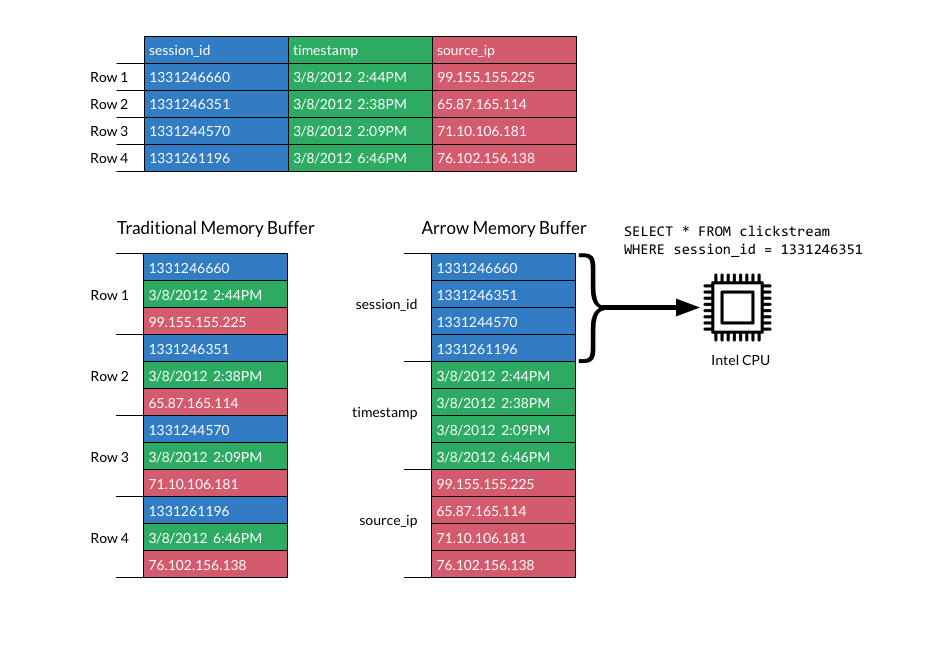

Structured types in Arrow can be seen as entries in a database, with a specified schema. While many databases are row oriented, data is column-oriented in Arrow:

The reasoning behind organizing data along columns instead of rows is that:

- compression should work better for data of the same type, (presumably, data should be relatively similar)

- many workloads only care about a few columns to perform their analyses, the other columns can be left at rest on disk,

- one can leverage vectorized instructions to carry operations.

This is the well-known structure of arrays (SoA) vs arrays of structure (AoS) debate.

With Arrow, the Person type defined previously could be implemented as the following structure of arrays:

|

|

A complete example is provided here.

Arrow tables

As hinted during this blog post, Arrow needs to be able to interoperate with industry provided or scientific oriented databases, to load all the interesting data into memory, as efficiently as possible.

Thus, it stands to reason for Arrow to provide tools that maps to operations usually performed on databases.

In Arrow, this is expressed as Tables:

|

|

The Table interface allows to describe the data held by some database, and access it via the array.Column type – a representation of chunked arrays: arrays that may not be contiguous in memory.

The code below creates a pair of records rec1 and rec2 (each record can be seen as a set of rows in a database.)

Each record contains two columns, the first one containing int32 values and the second one float64 values.

Once a few entries have been added to each of the two records, a Table reader is created from these in-memory records.

The chunk size for this Table reader is set to 5: each column will hold at most 5 entries during the iteration over the in-memory Table.

|

|

Executing the code above would result in:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

$> go run ./table-reader.go rec[0]["f1-i32"]: [1 2 3 4 5] rec[0]["f2-f64"]: [1 2 3 4 5] rec[1]["f1-i32"]: [6 7 8 (null) 10] rec[1]["f2-f64"]: [6 7 8 9 10] rec[2]["f1-i32"]: [11 12 13 14 15] rec[2]["f2-f64"]: [11 12 13 14 15] rec[3]["f1-i32"]: [16 17 18 19 20] rec[3]["f2-f64"]: [16 17 18 19 20] |

CSV data

Finally, to conclude with our quick whirlwind overview of what Go Arrow can provide now, let us consider the arrow/csv package.

As mentioned earlier, many analysis pipelines start with ingesting CSV.

The Go standard library already provides a package to decode and encode data using this comma-separated values (CSV) “format”.

But what the encoding/csv package exposes is slices of strings, not values of a specific type.

Converting string values to a specific type (float64, int, …) is left to the user of that package.

The arrow/csv package leverages the arrow.Schema and array.Record types to provide a typed and (eventually) scalable+optimized API.

|

|

Running the code above will result in:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

$> go run ./read-csv.go rec[0]["i64"]: [0 1 2 3] rec[0]["f64"]: [0 1 2 3] rec[0]["str"]: ["str-0" "str-1" "str-2" "str-3"] rec[1]["i64"]: [4 5 6 7] rec[1]["f64"]: [4 5 6 7] rec[1]["str"]: ["str-4" "str-5" "str-6" "str-7"] rec[2]["i64"]: [8 9] rec[2]["f64"]: [8 9] rec[2]["str"]: ["str-8" "str-9"] |

Conclusions

This post has only scratched the surface of what can be done with Go Arrow and how it works under the hood. For example, we have not talked about how the typesafe array builders and array types are generated: this is - BTW - an area where the Go2 draft proposal for generics would definitely help.

There also many features available in C++/Python Arrow that are yet to be implemented in Go Arrow. The main remaining one is perhaps implementing the IPC protocol that Arrow specifies. This would allow to create polyglot, distributed applications with an eye towards data science.

In the same vein, the Arrow Table, Record and Schema types could be seen as building blocks for creating a dataframe package interoperable with the ones from Python, R, etc…

Finally, Go Arrow tensors could be used as an efficient vehicle to transfer data between various machine learning packages (ONNX, Gorgonia.)

Gophers, follow the arrows and send your pull requests!